Little did James Chalmers and his missionary colleague Oliver Tomkins know, as they waded ashore at Risk Point on Goaribari Island, New Guinea, that they were walking toward their deaths. It was Easter Sunday, April 8, 1901, and the villagers rejoiced at their arrival, inviting them into the newly constructed dubu (a communal house for fighting men which could not be used without consecration by a human sacrifice) for refreshments. Yet the festive mood was in stark contrast to the piles of human skulls nestled around the crude wooden idols in the corner of the hut. Without warning, the natives attacked and dismembered their two visitors, passing the limbs to the women to be cooked, mixed with herbs. In those few moments, Chalmers and Tomkins passed from Easter faith to Easter presence.

Little did James Chalmers and his missionary colleague Oliver Tomkins know, as they waded ashore at Risk Point on Goaribari Island, New Guinea, that they were walking toward their deaths. It was Easter Sunday, April 8, 1901, and the villagers rejoiced at their arrival, inviting them into the newly constructed dubu (a communal house for fighting men which could not be used without consecration by a human sacrifice) for refreshments. Yet the festive mood was in stark contrast to the piles of human skulls nestled around the crude wooden idols in the corner of the hut. Without warning, the natives attacked and dismembered their two visitors, passing the limbs to the women to be cooked, mixed with herbs. In those few moments, Chalmers and Tomkins passed from Easter faith to Easter presence.

The Pacific islands were one of the first areas to be evangelized in the modern missionary era. Most of the indigenous population lived in primitive conditions, immersed in cannibalism, licentiousness, infanticide, and constant warfare. Yet by the end of the 19th century, most of this region had become Christian through the faithful and sacrificial service of many missionaries who proclaimed the gospel despite the constant threats of disease and death.

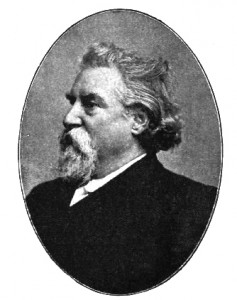

Chalmers, the son of a stonemason in the West Highlands of Scotland, was converted during the 1859 revival. Even as a boy he wanted to be a missionary to the cannibals, and eventually he arrived on the settled island of Rarotonga in May 1867, where he served with the London Missionary Society for the next ten years. He was a pioneer at heart and set off for New Guinea (modern day Papua New Guinea) to preach the gospel. For the next 23 years he labored up and down the coast, visiting 105 villages, 90 of which had never seen a white man, and establishing a chain of Polynesian teachers to continue the work. He always went unarmed, knowing this would allay native suspicions while leaving him defenseless in case of attack.

Chalmers, who outlived two wives, longed for the unreached to hear the gospel. “I dearly love to be the first to preach Christ in a place,” he said, and he had the joy of seeing communities transformed by the good news. Declining an offer to work as a government official, he declared: “Gospel and commerce, yes: but remember this: It must be the gospel first. Wherever there was the slightest spark of civilization in the Southern Seas it has been because the gospel has been preached there. The ramparts of heathenism can only be stormed by those who carry the cross.” Despite innumerable hardships, Chalmers counted it a great privilege to sacrifice everything for Christ.

At a time when many churches have championed the prosperity gospel with its “promises” of health, wealth, safety, and comfort, imitators of Chalmers are sorely needed. He sought neither personal protection nor glory; his faith did not rest on riches or long life. Instead James Chalmers lived with his eyes focused on heaven so that others might share his knowledge and confidence in the Savior. It cost him his life, but he would have been pleased with the exchange.

Dear sir

I have@gmail:disqus

Dear Sir

Do You have a picture of the LMS Missionary Reverend Oliver F Tomkins?

Peter

Did you get a picture of Rev Oliver Tomkins? I would like one too as he was a distant relative of mine.

The Goaribari affair

Early on the morning of 20 June, 10, the Administrator of British New Guinea, Judge C.S. Robinson took a revolver, walked out of Government House to the flagstaff and shot himself,

The events that lead to this suicide of an Administrator were dramatic and tragic. They began with the murder of the famous pioneer missionary, James Chalmers, the Reverend Oliver Tomkins and ten Papuans by villagers of Goaribari Island in the Gulf of Papua in April 1901.

The last brief phase of Tamate’s service to New Guinea was spent visiting existing mission stations. He was much encouraged by the arrival of a dedicated young helper, Oliver Tomkins. Together they planned an expedition to the Aird River Delta. The natives in that region were reputed to be fierce and unapproachable, even by Papuan standards. No white man had ever seen them. For a long time, Tamate had desired to make the dangerous trip there in order to win them for Christ. On April 4, 1901, the mission steamer sailed to Risk Point, off the shore of the village of Dopima.

Immediately natives surrounded the ship. Tamate promised to come ashore in the morning. The next day, both Tomkins and Tamate went ashore, saying they would return shortly for breakfast. After a certain interval had passed, as if by prearrangement, the natives who remained on the ship looted it, taking all of the stores of presents and Tamate and Tomkins’s belongings.

The captain alarmed by the prolonged absence of the two missionaries and by the conduct of the natives, was further concerned when he saw a large number of warriors getting into canoes. He suspected that the

Missionaries had been murdered and that the next targets were he and his shipmates. He sailed away to report to the governor. His suspicions were confirmed a short time later by British investigators and the testimony of captured natives from the guilty village. The missionaries had been clubbed, beheaded, and eaten. Both men were killed on 8 April 1901.

As soon as the news was received, Sir George Le Hume led an expedition which included a strong force of Constabulary to Goaribari. In a telegram to the Governor of Queensland, Le Hume told of what followed after the expedition landed! “Natives immediately commenced hostilities… We fired on them and occupied villages… total killed twenty-four and three wounded as far as is known… No casualties in our party except for native constable on sentry at night slightly wounded by sniping arrow… I decided to visit all villages on island and vicinity reported to be implicated… burning the large fighting men’s houses … I am satisfied this is last massacre of this kind on coast of British New Guinea… Regret nature of punishment but action absolutely necessary at once and best in end.

Le Hume returned to Goaribari in March, 1902, and the chastened people gave him a skull said to be that of Reverend James Chalmers. The leaders in the slaughter of the missionaries were still at large and Le Hume warned that he would return again and arrest them.

Sir George did not return. He left British New Guinea and became Governor of South Australia. He was succeeded as Acting Administrator by Judge Christopher Robinson, the chief judicial officer. Robinson was only thirty-five and keen to demonstrate his fitness for his new position. What better way than by arresting the killers of the martyred Chalmers, Tomkins and their Papuan followers? Judge Robinson set off in Merrie England in March, 1904 for Goaribari Island. With him was his private secretary, Arthur Jewell, and a junior RM, Army Henry Jiear. There was also a powerful force of Constabulary, thirty-nine in all, under the command of a recently appointed Commandant, W. C. Bruce. Bruce, a huge man was a soldier by profession who believed in the virtues of discipline and the military life.

The Goaribari must have watched the approach of Merrie England with dismay and suspicion, Le Hume had promised that he would return and make arrests; was this now going to happen? In a letter written shortly before his suicide, Judge Robinson said that the object of his visit to Goaribari was “to capture the ring-leaders … and obtain possession of the late Mr. Tomkins’ skull, …” In consultation with Henry Jiear, the only one of the whites with any real experience, Robinson decided that the arrest of the wanted men would be made on the deck of Merrie England after the Goaribari had been enticed on board. Jiear was given command of the operation. Henry Jiear, though a junior RM, had plenty of field experience. Soon after he was appointed RM of the West Division, the Bugi detachment of Constabulary, after Corporal Kesavi was mauled by a previously unknown inland tribe. The Corporal was injured and the Bugi police were forced to retire, carrying Kesavi on a rude litter.

When Jiear heard of this, he went in with a tough detachment of Constabulary. When the wild tribesmen attacked, nine were shot dead, Corporal Kesavi eventually recovered.

In November, 1903, Jiear got word of fierce fighting between the Wabada and Sibarubi tribes, on the Bamu River. He marched to the scene with nine of his Constabulary. The Wabada, the aggressors in the fighting, took refuge in a deep swamp, and Jiear and his men went in after them.

While crossing a log bridge over a small creek, Constable Dainu was wounded by in arrow fired by a concealed bowman. A local native whom Jiear had temporarily engaged as a special constable was savagely butchered Jiear reported: “I was shocked . . . to come across this man’s dead body, minus the head and arms. His clothing lay near at hand and two arrows were stuck in his body, one having penetrated the lungs and the other having entered near the groin…

Later in the afternoon the Sergeant’s party returned with one of their number in a dying condition, one constable was hit in the leg and disabled, and one man of the Sibarubi was shot in four places by arrows, The unfortunate man was in the throes of death… and I could do nothing to save his life. Two arrows had struck him in the stomach, one in the eye, the fourth sticking in his left shoulder . . .” Next day the Constabulary stormed into the swamp and drove the belligerent Wabada out. Two of the leaders were captured by Constables Dainu and Yapia, and two warriors were shot dead. Henry Jiear had amply demonstrated his coolness in the face of danger, which makes the events on the Merrie England that day — 6 March, 1904 — the more surprising. A Royal Commission was later held into the affair, and the Royal Commissioner, Charles Murray, summarized what happened in his Report.

A large number of Goaribari — as many as 600, though estimates differed — came out to Merrie England. lake, one of the wanted men, was persuaded to come on board and was seized, together with a number of others. “Almost at the same time,” Murray reported, “some of the native police opened fire with their carbines on the natives in their canoes lying round about, from which arrows had been discharged at the ship; the firing was joined in by the Acting Administrator, and, to a small extent, by a few of the officers and crew. The natives retreated at once, but several were killed or wounded. In a few minutes, the firing ceased.”

It is clear from the evidence that there was a total breakdown of discipline and control on Merrie England that day. There seems little doubt that Judge Robinson panicked when the shooting began. A statement made by Henry Jiear told heavily against Robinson. Jiear had been placed in charge of the arrest plans. He said that he had told Robinson that he would personally conduct the arrests of lake and another wanted man, Ema. He was preoccupied with this task when he heard the first shots. Jiear swore that he saw a smoking rifle in the Administrator’s hands. Robinson denied having ordered the shooting; he said that he “saw police firing and thought they had been ordered to do so, and I fired three shots …”

Jiear told the Royal Commissioner that he was “astounded” that firing had taken place without his orders, seeing that he had been given charge of the operation.

Commandant Bruce denied having ordered the Constabulary to open fire — in fact, he had ordered them to stop. When asked if he had taken any part in the affair, Bruce replied: “No. I am not a murderer.” Arthur Jewell, Robinson’s private secretary, was a rather nervous and excitable young man and he swore that he had seen Robinson personally shoot twenty Goaribari. ”He was firing his rifle as fast as he could load the magazine. He was firing at natives even when they were struggling in the mud trying to get away … it was a most treacherous murder.”

The Royal Commissioner finally concluded that some 260 shots were fired. “Out of these shots a number would, of course, be ineffective, especially as the native Police on board were very bad marksmen, with the exception of the Daru detachment, who were fair shots. From the whole of the evidence on the subject it would appear that at least eight natives were killed … it is probable that the more or less seriously wounded amounted to at least some low multiple of eight . . .-

The Royal Commissioner concluded that whatever the justification for it. the shooting had continued too long. Firing had continued after the Goaribari were in full flight, and at swimmers trying to escape.

“If the Acting Administrator had been able to give his own account … he may have thrown some new light upon his actions. As it is, the fault, as he puts it himself, must rest with him; but it is one rather of over zeal and want of judgment than of anything approaching to conscious or willful departure from the absolutely straight path befitting the high offices he held.”

For Judge Robinson had killed himself before the inquiry began. Soon after Jiear made his statement throwing the whole of the blame on Robinson, the missionary, Charles Abel, had left his station at Kwato, gone to Brisbane and demanded a Royal Commission into the killings. Abel had absolutely no first-hand evidence of what had occurred. But this was enough. Sensational — and largely inaccurate — accounts of the “Goaribari Massacre” appeared in newspapers all over Australia and overseas, blaming Robinson. He was abandoned by the Australian Government, suspended from his position pending a full inquiry.

As a lawyer, Robinson knew how damning were the accounts of Jiear and Jewell. Just before he killed himself, he wrote a pathetic letter: “It is clear to me that it was a grave error of judgment on my part to have attempted any arrests on the Merrie England, I was of the opinion, and am of the opinion still, that the firing was both justifiable and necessary. I think now that in the excitement which prevailed a good many more shots were fired than would have been if everyone who took part had remained cool and collected.

“I can only repeat that no blame can rightly be attributable to anyone in connection with it save myself only. I was primarily in authority, and as I am solely responsible for the course which was followed, I am also responsible for the consequences of it.”

Honourable in his actions to the end, Robinson said that Abel “has attributed to me words and expressions which I, at all events, have the satisfaction of knowing, I never uttered.” Of Jiear, he said: “Mr. fear’s statement contains much of misrepresentation and several untruths . . .”

It can never, now, be known who in the Constabulary fired the first shot. It is surely ironic that literally hundreds of wild tribesmen had been killed by Constabulary bullets in many affrays in the Northern and other Divisions over the preceding years, without attracting a single adverse reference in Australian newspapers

The Goaribari Affair was different, for among those firing at tribesmen was an Administrator. That made it “news”

There is a stained glass window to their memory in the college chapel at Vatorato, Rarotonga including a copper beating at the Ela United Church in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. The news of Chalmers and Tomkins murder made headlines all over the world. Those who had worked closely with Chalmers were shocked and grieved at the news of his death, but felt strongly that he would have wished to die as he did – engaged in service to the natives of New Guinea. As an old friend wrote:

“Hitherto God had preserved him; now he allowed the blow to fall, and His faithful servant to be called up home.”

And on 18th March 1902 in Edinburgh, Scotland, a writer named Cuthbert Lennox wrote and published a book called “JAMES CHALMERS OF NEW GUINEA” and quoted Mr. John Oxenham’s expression in the confidence that:

“His name,

Shall kindle many a heart to equal flame,

The fire he kindled shall burn on and on,

Till all the darkness of the lands be gone,

And all the kingdoms of the earth be won,

And one.”

The writer will rejoice if this little volume, like a torch, renders humble service in helping to pass on the kindling flame to “many a heart.”

Please I need some journals of James Chalmers first encounter at Iokea Village in Gulf of Papua New Guinea

I really can’t sign on to one religion intruding on anthers religion and wondering why they get killed. Please reply

BTW I am not religious I belive when i did I will go to hell.

The exact date of arrival of Chalmers at Moru bay,Iokea village.PNG.

There has been inquiries about descendants/ relatives of Chalmers and Thompkins for a reconciliation event in the village they were murdered in Goabari. The men didn’t have children. I heard about the event from the Principal of Takamoa bible college in Rarotonga. (The Cook islanders were a major missionary force with Chalmers at that time.)

Wendy Rowan Aus

The Dopima peace & Reconciliatio Treaty Mission is now ready to proceed with peace process & negotiations, subject to the availability of funds. It is anticipated that this peace process will be funded under State – Church partnership program. A major fund raising drive will also be made to complement the State / Church partnership program. Revd Siulangi Solomona Kavora is the Chairman of Dopima Peace & Reconciliation Committee. He is charged with the responsibility of facilitating & overseeing the Dopima Peace Process.

Will keep you posted on further updates.

Joseph Mangabi

I am interested in reading some journals or diaries of Rev Albert Peace who who was at Kerepuna in Papua New Guinea