Like the fellow who thought he’d be crossing visible longitude lines on his ocean voyage to Europe, some may think that the chapter and verse divisions were on the sheet when apostles such as John (or psalmists such as David) wrote down Scripture. But no, they wrote letters and poetry and Gospels and other history without numbering. Those markers were added centuries later. Indeed, when Jesus referred to Exodus 3:6 in Mark 12:26, He simply located it in “in the passage about the burning bush.” Neither the “12:26” nor the “3:6” were yet in place.[i]

Like the fellow who thought he’d be crossing visible longitude lines on his ocean voyage to Europe, some may think that the chapter and verse divisions were on the sheet when apostles such as John (or psalmists such as David) wrote down Scripture. But no, they wrote letters and poetry and Gospels and other history without numbering. Those markers were added centuries later. Indeed, when Jesus referred to Exodus 3:6 in Mark 12:26, He simply located it in “in the passage about the burning bush.” Neither the “12:26” nor the “3:6” were yet in place.[i]

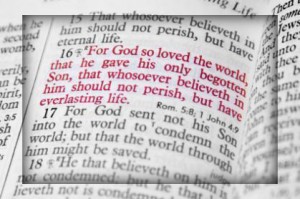

To make a long story short, biblical scholars were making divisions of one sort or another in the centuries following the books’ original composition, but it wasn’t until the early 1200s that we got our current chapter setup, thanks to Archbishop of Canterbury Stephen Langton. As for the verses, Jewish scribes had already done work on the Old Testament around the year 900, and their work was wedded to Langton’s. But the Church had to wait another 300 years for its New Testament breakdown, performed by a French-born printer, Robert Estienne or Etienne (also know by the Latinized version of his name, “Stephanus”).

He was a Protestant refugee in Geneva when he decided to construct a concordance for the Greek New Testament, but he found the broad A, B, C, D divisions unwieldy. So he inserted verse numbers, and the product was an overnight success. This isn’t to say his choices were free from criticism. Though the original writings, whether by Moses, Luke, or Peter, were free from error, that same inerrancy did not extend to Langton and Estienne, as useful as their work has proven to be.

For instance, most modern translations group 1 Corinthians 11:1 with the closing verses of chapter 10, under such headings as “Christian Liberty” (HCSB), “The Believer’s Freedom” (NIV), and “Do All to the Glory of God” (ESV). Most simply think that 11:1 belongs with the previous chapter. And other critics have objected to the way Estienne cut up single sentences, as with the opening words of Romans. Depending on where the translator puts the period, the first sentence of that epistle runs four (ESV; NIV) or six verses (HCSB).

Still, it’s hard to imagine how we could get along without these markers, as we cite or quote “Psalm 23” or Paul’s instructions regarding the believer’s relationship to the state in “Romans 13:1-7.” They’ve proven most helpful as we’ve made the most of the fact expressed in 2 Timothy 3:16-17: “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be competent, equipped for every good work.”

So one hears, “Okay class, let’s open our Bibles to today’s text. I’d like each of you to read three verses as we go around the room.”

<!-- RefTagger from Logos. Visit http://www.logos.com/reftagger. This code should appear directly before the tag. -->

//

//

Thank you for pointing out how the “chapter and verse” divisions were not put in the Bible by God!Brad