Counseling student Janie Pillow was sitting at a library table at Reformed Theological Seminary (RTS) in Jackson, Mississippi, when the student next to her made a sound she can still remember more than 20 years later.

The student—an older man, a ThM candidate from Africa—“moaned a moan that gives me chills to this day,” Pillow said. “Then he whispered under his breath, ‘I think that’s my son.’”

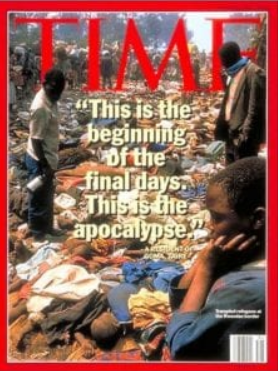

Pillow followed his gaze to the table. “There were Time and Newsweek magazines, but one had—as far as you could see—bodies piled up.”

The bodies belonged to Rwandan refugees who were trampled as they raced to escape the continent’s largest genocide. (Between April and June 1994, about 800,000 people—mostly Tutsis—were killed.)

Pillow took her fellow student to the student administrator’s office, and they called the Red Cross. Six weeks later, confirmation: The boy in the photo was his.

Horrified and livid, Pillow called one of her favorite professors. Richard Pratt spent most summers on mission trips to other countries, and often stayed late after class to tutor international seminary students.

“She said, ‘We have to stop doing this,’” Pratt remembers. “I said, ‘Doing what?’”

“Sending international students to the States for theological education,” she replied. She’d been worrying about this for a while, having spent the last year in a prayer group with lonely and anxious international students.

“I was praying that my oldest son wouldn’t get hurt in a football game,” Pillow said. “They were praying that God would be with their wife who had just been raped, or praying for those whose homes had been burned down, or for their children who had their hands cut off.”

Pratt asked what she wanted to do.

“I want to put seminary in a box and mail it to them,” she told him. “If I can get the money, can you get the box?”

“That’s easy,” he said. “I can get the box.”

But it wasn’t easy. At times, the endeavor seemed ridiculous—too expensive, too hard to translate, too difficult to transport.

“Richard quit a million times,” Pillow said. “I quit a million times.”

But neither ever did. Pratt taught himself a video program and made VHS tapes in his bedroom. Pillow juggled seminary homework, her six kids, and asking strangers for funding.

And over the past 20 years, Third Mill has created 119 lessons for 27 seminary courses in five core languages. The lessons have made their way into every country in the world. Numbers aren’t easy to track, especially in countries hostile to Christianity. But over the past five years, nearly 700,000

This summer, Third Mill finished creating enough courses that a pastor anywhere in the world could earn a master’s degree in Bible and theology. From a solid Reformed perspective. For free.

“The biggest joy for me has been knowing that people I will never see until I get to heaven have had this wonderful opportunity to learn the true gospel, instead of a paganized version of it,” Pillow said. “To know that good theology is being taught about the true God and his works and his laws and his love thrills me better than anything else in the whole world.”

Spreading Seminaries

In past decades, if you wanted a solid theological education (and had enough money), you went to school in Europe or North America. Of course, if you lived in a developing country, that was far easier said than done.

Denominations tried to solve this problem a few ways: by sending missionaries, by building seminaries, and by bringing pastors to study in the United States.

“Traditional strategies are important and should continue, but the need is far too great to be met with these strategies alone,” Third Mill’s website states. That’s hard to argue against—the number of Christians is predicted to grow from 2.2 billion in 2010 to 2.9 billion in 2050, according to Pew Research Center.

Most of that growth is happening in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, where the fewest opportunities for theological education exist, Pratt said. In 1950, there were just 70 to 80 pastoral-education or theological schools in the entire continent of Asia.

That number has grown—thousands now attend evangelical seminaries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. But even in 2010, there were at least five-times as many seminaries per 10 million Christians in North America as there were in Africa, according to the Center for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. More than half (58 percent in Africa, 62 percent in Latin America) of respondents said there were not enough theological schools to meet the need in their region.

That number has grown—thousands now attend evangelical seminaries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. But even in 2010, there were at least five-times as many seminaries per 10 million Christians in North America as there were in Africa, according to the Center for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. More than half (58 percent in Africa, 62 percent in Latin America) of respondents said there were not enough theological schools to meet the need in their region.

“In the vast majority of where the church is growing really fast—parts of Asia and Africa—many get their teaching by watching American Christian television or God TV from the UK,” said Pratt, who began traveling every summer to teach and preach after a mission trip with Cru in 1985. “Where the church is growing the fastest in the world, there is the least opportunity for Christian leaders to learn the Bible and sound theology.”

When Pillow suggested boxing up seminary, he immediately saw the advantage. Before Third Mill even got going, he was already expanding the scope.

Video Animation

In 1998, the Prince of Egypt film was released in theaters. Val Kilmer voiced Moses, Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey sang the theme song, and Pratt gave religious advice. (He was one of about 600 advisers, but Pratt is the reason the film ends at the Sinai instead of the Red Sea. “The story isn’t just about freedom from something, but to something,” he told filmmakers.)

When one of the donors found out, he told Pratt, “I want you to do something like you did with [filmmaker Steven] Spielberg—make a movie.”

Pratt counter-offered. He wanted to make videos that showed illustrations—that was how he liked to teach—and dropped in short interviews with experts. He wanted a host, photographs, charts, and maps. Less DreamWorks animation, more History Channel documentary.

“I went to a low-end studio in Orlando and told them what I wanted,” Pratt said. “They said it would cost $6,000 to $10,000 a minute. That was before mobile phones, so I had to go home and find a calculator. My goal was a two-year program, and I discovered it would take about half a billion to do it.”

Nope, he thought. He called the donor and asked for the money to buy a computer instead.

“I spent a year and a half in my back bedroom, learning how to make digital video and animations,” he said. “Then I made a demo to show people how it could be done—how effective it could be. By God’s mercy, people began to support it.”

But not everyone. Some said it was too expensive, or that it couldn’t be translated well, or that transporting bulky VHS tapes would be impossible.

On top of the practical objections, there were theoretical ones: “Leftover from the 1960s and 1970s missiology in America was the belief that even if you can make it, and translate it, and deliver it, [the students] will not want it, because it’s from America,” Pratt said.

But the way he saw it, somebody was going to take the gospel to the global South and East—“either prosperity gospel doctrine or worse. . . . It’s not a question of whether the West is going to influence Eastern Christianity, but what kind of influence they’ll have.”

Simple Language, Not Easy Concepts

The influence Third Mill is aiming for is “soft-touch Calvinism,” Pratt said. He’s an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church in America, and Third Mill “has a commitment to the Westminster Standards.”

But Third Mill also likes to include as many theological experts as possible. The classes feature video interviews with 370 different professors and Christian leaders from around the world, who speak on their areas of expertise.

Featuring academic experts from different ethnicities and nationalities lends Third Mill credibility with students and helps to keep the curriculum from feeling overly Western, he said.

“We present different perspectives on non-salvific issues that Christians sometimes disagree about,” director of curriculum Cindy Sawyer said. “We also offer companion lessons that include interviews with several professors answering questions on topics related to the lessons—topics that will help students better understand the content of the lessons.”

Even then, Third Mill is careful with what it presents as legitimate areas for disagreement. “We get to pick and choose,” Sawyer said. “We aren’t putting anything in there that is heresy, or that we strongly disagree with.”

Explaining those viewpoints is part of Third Mill’s commitment to a robust theological education.

“Sometimes people jump into making it easy for [international students], so they say something like, ‘Noah was a good man who went on the ark with the animals,’” Sawyer said.

That’s not what Third Mill wants. They’re aiming for clear and simple language—“easily translatable”—but not easy concepts.

“We have a really good process of taking difficult theological concepts and not dumbing them down,” Sawyer said.

The result is material sharp enough to be used in Western seminary classrooms, but clear enough that “it’s understandable by someone with an eighth-grade education in the fields of Argentina,” she said.

If you just thought, Hey, maybe that’s something I could use, you aren’t the only one. Third Mill has started hearing from high-school teachers, prison chaplains, and Bible study leaders who wanted to use the curriculum.

The courses weren’t exactly designed for that use—the videos are usually an hour or longer—but Third Mill is “available to anyone who desires to study the Bible and theology more deeply,” director of communications services Darlene Perry said. Third Mill is in the process of creating application guides to help group leaders work more effectively with their materials.

“It’s exciting what God does,” Sawyer said. “You set off to do one thing, and he says, ‘Great, but let’s also go here and here and here.’”

For the World

When Pratt first started, he was still employed by RTS—essentially, earning a salary from one seminary while compiling course content for students who could never enroll in a seminary graduate program.

“We are very positive, very supportive,” said RTS chancellor emeritus Ric Cannada, who headed up the RTS system from 2002 to 2012. “The quality and content of his stuff is great. We promote it, talk about it, encourage people to use it. There are just a lot of settings where people would like a [seminary] degree, but can’t for one reason or another. And Third Mill is an excellent alternative.”

One of those settings is Zimbabwe, where a Presbyterian church went online a few years ago, looking for “evangelical, reformed, biblically based and theologically sound resources” for its leaders and members, City Presbyterian Church teaching elder Jorum Mugari said.

“We needed a resource that would not require us to spend a lot of time preparing notes before actually engaging the students,” Mugari said. “We also needed a resource that would not cost the church an arm and a leg. Above it all, we needed a resource that was totally committed to the Bible and the Christ of the Bible, and yet flexible to the needs and context of Africa. . . . Third Millennium was an above-the-rest resource which suited us best.”

City Presbyterian began using Third Mill to train its own pastors. But “many pastors in Zimbabwe lead churches without any theological education,” Mugari said. “We began attracting other leaders from different denominations.”

Mugari, who is a professor at the Theological College of Zimbabwe (TCZ), is “keen on” this.

Third Mill “gets me to train pastors who have no money to qualify to enter TCZ’s formal ministerial training,” he said. “Also, most of the pastors who take classes with me on Saturday mornings do not have enough qualifications or high-school education to be at TCZ, where I teach on a daily basis.”

City Presbyterian paired up with Birmingham Theological Seminary to offer a certificate in Christian ministry using Third Mill. Today, close to 60 students are taking Third Mill courses through the church, which plans to start 10 more cohorts in the spring.

City Presbyterian paired up with Birmingham Theological Seminary to offer a certificate in Christian ministry using Third Mill. Today, close to 60 students are taking Third Mill courses through the church, which plans to start 10 more cohorts in the spring.

A St. Louis church is also using Third Mill to train African leaders. New City Fellowship worked through ministry partnerships to enroll about 20 students in the Congo and another 20 in Togo, with plans to begin training in Rwanda in January.

But executive pastor Barry Henning is also using it in St. Louis. About 15 church members—doctors, lawyers, ministry leaders, carpenters, repairmen, and college-age students—watch the videos during the week and then attend a weekly two-hour class. Henning levels it up—”a bit more intense study, more one-on-one time for discussion, and additional readings”—when he uses Third Mill to train two Congolese immigrants for pastoral ministry.

“I love it,” Henning said. “The breadth of teachers from across the world who are all biblically sound and well-trained, offering their resources in a highly accessible fashion—both in terms of the substance of the lectures and also the format of video, audio and written formats—is a blessing from God for the next generation of leaders across the world.”

Available Everywhere

One of Coca-Cola’s earliest slogans was “around the corner from everywhere,” and “that’s what we want—utter ubiquity,” Pratt said. “Our model is like electricity—everybody wants it and needs it. Let’s put it out there.”

But it’s going to take some time before Third Mill’s capacity can catch up to its vision.

“One of the biggest challenges is that we can’t say yes to every opportunity,” vice president of strategic projects Greg Perry said. The going can be slow—Third Mill distributes its resources through local pastors’ councils, church-planting networks, or mission organizations, and it takes time to learn the peculiarities of each one. Not only that, but Third Mill’s staff has been built around content production. Adding distribution capacity will require more people with different skills.

“It’s growing pains,” Perry said. “It’s the kind you want, but it is painful.”

Flipped Classroom

Before Perry came on staff at Third Mill, he used the curriculum to help train resettled Congolese refugees he was working with in St. Louis. But he also used it at Covenant Seminary, where he was teaching both online and traditional classes.

“What was so important for me as a professor was to connect the great heritage of the church and the Holy Spirit’s work with what’s happening on the streets,” he said. That meant Perry’s greatest role wasn’t to deliver content, but to “be a bridge.”

“I used the flipped-classroom approach,” he said. “They could watch the videos [on their own], and then I could use classroom time to focus more on formation of ministry skills, the ‘So what?’ questions.”

One example is the imagery of heavenly worship in Revelation 4–5. Perry asked students to view the Third Mill course on Revelation, then led a classroom discussion about intercultural worship in the city. He also drew on Third Mill images of the renewal of earth as a global temple in Revelation 21–22 to talk about “the importance of cultural and community development work as a penultimate expression of kingdom mission.”

Perry sees resources like Third Mill as a way for seminaries to pop out of their “academic bubble” and to get students into real-life ministry, while still under the guidance of a professor.

That’s what Calvin did in Geneva, Pratt pointed out. “Calvin made students serve in hospitals and work with refugees and live with elders. It was remarkable.”

Whether or not other professors are following Perry’s approach, Third Mill has seen a few Western seminaries interested in using their curriculum to offer off-campus degrees.

“Schools are realizing the need is so great that they need to partner with us to reach people they never could have before,” Pratt said. “So far God has blessed us in that we aren’t seeing a spirit of competitiveness [between Third Mill and brick-and-mortar seminaries].

“I remind people that the need is much greater than you’ll ever fulfill. We aren’t competing for anything here. If we are going to bring good, sound, gospel education to every leader of the church, then we need to work together.”

Cannada agrees. “I don’t see it as an either-or, but both-and,” he said. “The need is so big out there. We need more and more good Reformed theological education, not less.”

Big and Complex

“We get letters every day,” Pillow said. Her favorite was “one from a man in solitary confinement serving a life sentence. His writing was hardly legible. He wrote and thanked us—he had been converted, his life had been changed, and he felt that rather than serving a life sentence, he was free.”

The task hasn’t been easy—it’s difficult to find good animation artists. Writers need to have theological understanding, the skills to contextualize concepts globally (no American illustrations like comparisons to baseball or football), and the ability to engage both those with an eighth-grade education and those with a post-secondary degree. And funding is always a challenge.

But the rewards are enormous.

“God is definitely working here, because we look around and there’s a lot of stuff that should not have worked out that did,” Sawyer said. “I love what I do. I love what we’re doing.”

The world’s need for gospel-centered theological education is too big and complex for any one organization to carry. But Third Mill is lending a hand.

“By God’s grace,” Pratt said, “we are making enormous strides in meeting one of the greatest needs in the kingdom today—teaching the Scriptures and sound theology to Christian leaders everywhere.”

Originally posted on The Gospel Coalition website on November 26, 2018. Republished by permission.

Sarah Eekhoff Zylstra is senior writer for The Gospel Coalition. She earned her master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University.