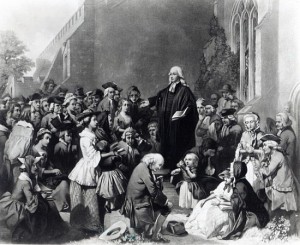

On a bright April day in 1743, John Wesley stood preaching to an open-air crowd the great truths of salvation. The rag-tag congregation, who had come out into the countryside to hear this famous preacher, listened enraptured to his message of regeneration and new life. Just then, an old drunk rode his horse into the middle of the crowd, rearing the beast up and shouting all manner of curses and bitter words at the preacher. Wesley, who by  this time was used to such displays, tried to ignore the man and continue his sermon. That course, however, quickly proved impossible when the fool drew his horse up and, still spewing venom at Wesley and his gospel, tried to run down some of the crowd. People scattered, no one was trampled, and in a few minutes the situation was brought under control. Speaking later to some local residents, Wesley was shocked to learn who the old wobbly drunk was: a clergyman from a neighboring parish church!

this time was used to such displays, tried to ignore the man and continue his sermon. That course, however, quickly proved impossible when the fool drew his horse up and, still spewing venom at Wesley and his gospel, tried to run down some of the crowd. People scattered, no one was trampled, and in a few minutes the situation was brought under control. Speaking later to some local residents, Wesley was shocked to learn who the old wobbly drunk was: a clergyman from a neighboring parish church!

After months of open air preaching, Wesley had learned to expect such opposition. Anglican rectors early on refused to allow him to preach from their pulpits, so Wesley finally forsook the beautiful established churches altogether and took his message first to the church cemeteries and then to the countryside. Thousands of hearers followed him, but even there in the remote regions, he could not avoid trouble. Hecklers and other troublemakers hounded him wherever he went, running through the crowds screaming, banging pots and pans together, or even throwing rotten eggs and over-ripe fruit at him to silence his preaching.

Wesley’s message evoked such a vehement response because he called on Christians to do more than merely recite their creeds once a week. He expected the gospel of Christ to change their hearts and, from there, to reform their lives and ultimately their entire society. “Christianity is essentially a social religion,” he said, and “to turn it into a solitary religion is indeed to destroy it.”

With that conviction, Wesley publicly addressed at one time or another nearly every social and cultural issue of his day. He took aim, for example, at Britain’s thriving slave trade, calling it the “execrable sum of all the villainies” and insisting on the “equal and priceless value” before God of “every immortal soul,” including blacks. He also abhorred war and worked tirelessly to urge a peaceful solution to the conflict with the American Colonies in the 1770s. He rejected the common notion that religion could be kept separate from business, for unless it was permeated with Christian values and dedicated to Christian goals, Wesley thought, business could not help but be turned to diabolical ends. Wesley railed against the social and cultural degradation of his day, championing the poor, castigating Britain’s aristocracy for wasting and hoarding their goods, condemning the liquor traffic which had reduced the nation’s labor force to a drunken stupor, and rebuking lawyers and politicians for using the law to gratify their own greedy desires. Secular or religious, sacred or profane, no department of human affairs was exempt from the word and command of God.

Wesley preached over 40,000 sermons during his life and traveled more than 200,000 miles, mostly on horseback. When he died at the age of 88, his tireless efforts had made Wesley an internationally revered figure. His Methodist movement had won official recognition by the government, and its influence had spread far beyond the shores of Great Britain.

Wesley suffered scorn for his down-to-earth, practical Christianity, but the Lord used his faithful, persevering labors to build a worldwide Christian movement. Even if faithful Christians disagree about how exactly to apply the conscience of Christianity to society, all can benefit from a careful perusal of the life and legacy of John Wesley.

————————–

Endnotes:

J. Wesley Bready, England: Before and After Wesley: The Evangelical Revival and Social Reform (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers).

Besides the 294 preachers and 71,668 members on the Isle, there were 198 preachers and 43,265 members in America, as well as some 5,300 new Christians brought to Christ by 19 missionaries spread throughout the world. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 3rd ed., s.v. “Wesley, John.”