Jesus, Truth, and Logic

I recently read that Jesus didn’t believe the laws of logic, in particular the law of non-contradiction. Apparently the laws of logic are at home in an Aristotelian worldview, whereas Jews had no problem simultaneously holding conflicting ideas (e.g., Proverbs 26:4-5). The author also suggested that truth and knowledge are entirely personal (thereby rejecting or denigrating propositional truth).

I was shocked by the number of people who agreed with the notion that Jesus wasn’t “Aristotelian.” Of course Jesus wasn’t an Aristotelian, but whether he believed the laws of logic is an entirely different matter. What are we to make of Jesus’ relationship to truth and the laws of logic? Given our cultural moment, with the widespread denial of objective truth, the church needs to have clarity on this important question.

Personal vs. Propositional Knowing?

First, propositional knowledge in no way conflicts with personal knowledge. God did give us a book full of propositional truths as the primary means through which to know him after all. Like in any relationship, communication is key to our intimacy with God. He speaks to us using words in the form of sentences we can understand and vice versa. Jesus, the full revelation God, came speaking (Hebrews 1:1-2). He is the Word who uses words. So, propositional truth claims do not conflict with, but complement, personal knowledge. We get to know God, personally, in large measure through propositions (e.g., the word and prayer).[1]

Jesus and the Laws of Logic

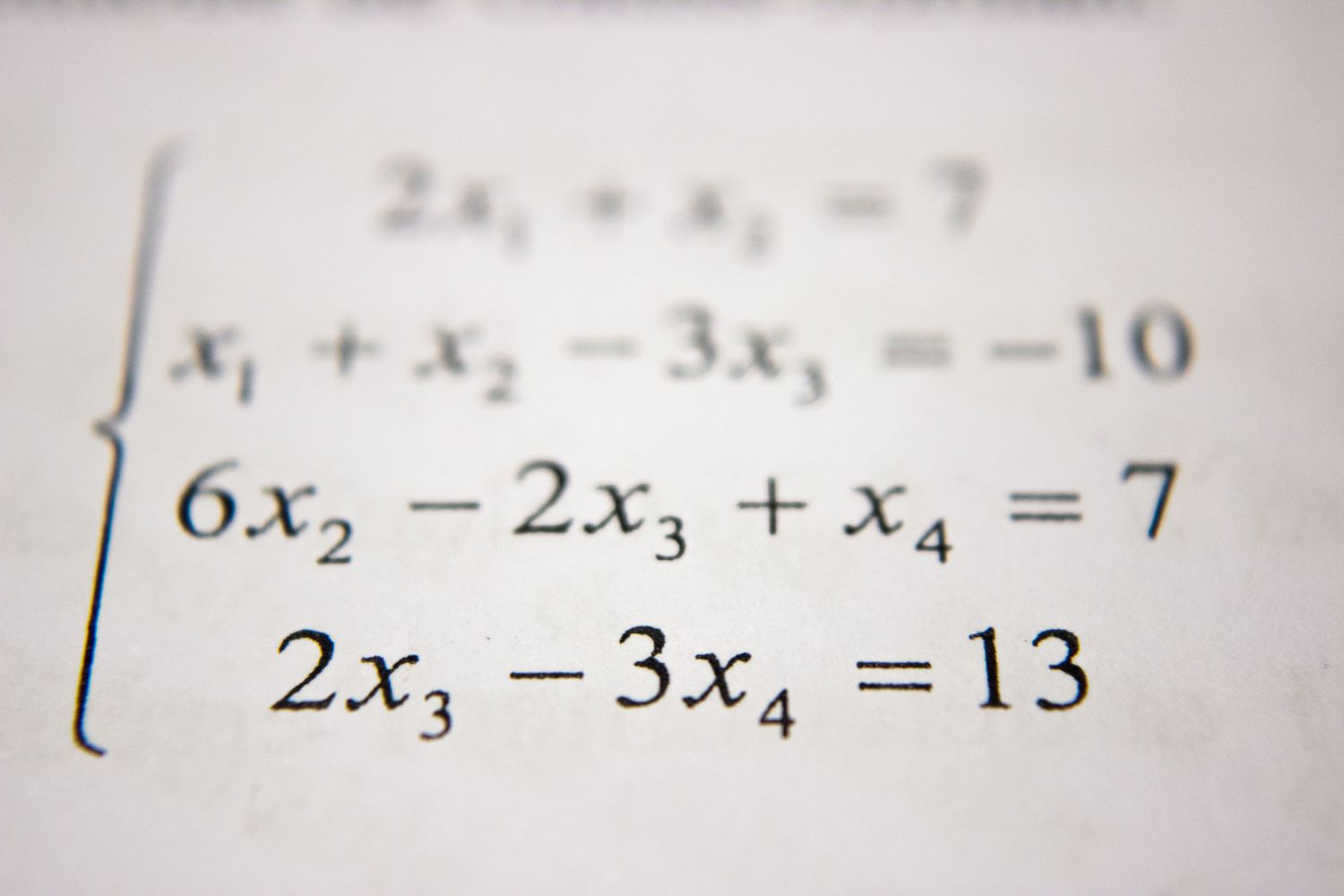

What about the laws of logic, in particular the law of non-contradiction? Does Jesus believe the laws of logic? By way of reminder, three fundamental laws of logic are said to govern rational thought:

- The law of identity, which states that a thing, including a proposition, is identical with itself (P is P).

- The law of non-contradiction, which states that contradictory propositions cannot both be true in the same sense at the same time (P is not non P).

- The law of excluded middle, which states that a statement is either true or false—there is no third option (either P or non-P).

Focusing on the law of non-contradiction, imagine one person says that George Washington is president and another person says that George Washington is not president. Do we have a contradiction? It depends. If both people said this in 1790 and were both referring to the president of the United States, then we would have a contradiction. In that case, both statements could not be true. George Washington either was or was not president of the United States in 1790—there is no other option. But, if one person was saying that George Washington was president of the United States in 1790 and the other person was saying that George Washington was not the president of his college in 1790, then there is no contradiction. They would not be using the word president in the same sense. There also wouldn’t be a contradiction if the person affirming George Washington’s presidency lived in 1790 and the person denying George Washington’s presidency lived in 2021. In that case, they would be using the word president in the same sense but not at or referring to the same time.

As you can see, an apparent contradiction differs from an actual contradiction. Contrary to what was suggested above, Scripture supports no actual contradictions. The denial of the law of non-contradiction isn’t Jewish or Christian; it’s Buddhist or Hindu. Whereas pantheistic religions often ironically deny any distinctions (believing all reality to be one), the Bible everywhere presupposes and makes use of the laws of logic.

For example, when Proverbs says, “Do not answer a fool according to his folly,” and then turns around and says, “Answer a fool according to his folly” (Proverbs 26:4-5), the author is speaking of answering a fool according to his folly in two different senses. On the one hand, he is saying to expose the fool’s foolishness. On the other hand, he is saying not to respond to foolishness with more foolishness, either in the content or manner of our response.

Of course, if you believe that contradictory statements can both be true, why write an article claiming Jesus wasn’t an Aristotelian—unless of course you are willing to grant that Jesus was or could also have been an Aristotelian (a blatant contradiction).

Another problem with equating the laws of logic exclusively with Aristotle is that Aristotle didn’t invent the laws of logic; he discovered them. People all over the world knew the substance of the laws; Aristotle was just the one to formalize them. In fact, the laws of logic, like mathematical truths (e.g., 2+2=4) or moral truths (e.g., murder is wrong) are necessary truths. That is, they are true in all possible worlds, including worlds where Aristotle did not exist. Indeed, the laws of logic are grounded in the mind of God (not Aristotle).[2] I.e., They are divine thoughts. It would be accurate to say, then, that Aristotle was “thinking God’s thoughts after him” thanks to general revelation.

So, did Jesus believe the laws of logic? Yes, Jesus most certainly believed the laws of logic because Jesus is omniscient and therefore believes all true propositions and does not believe any false propositions. In his divine nature, the laws of logic are his “intellectual property.” Jesus didn’t follow Aristotle’s line of thought in believing the laws of logic; rather Aristotle was following Jesus’ (the eternal Logos’) line of thought in adopting the laws of logic, and so should we.

Jonathan Darville is a former Global Master Trainer with The Center for Leadership Studies and Co-Leader of the New York branch of Models for Christ (an international non-profit bringing the gospel to the fashion industry). This post first appeared on the blog of the Center for Faith and Culture at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary.

[1] Of course we also know God through his actions. Note, whether through words, actions, or events, we cannot know God savingly apart from the work of the Spirit (1 Corinthians 12:3).

[2] See Greg Welty and James Anderson’s “In Defense of the Argument for God from Logic.”