We do need to be able to recognize evil, but it is not always easy to do so. Intriguingly it was when the American psychiatrist Scott Peck was researching his book on evil, People of the Lie, that he became a Christian. He asserts that when counsellors encounter evil in their counselling, they need to be able to name it. His examples are instructive because evil often tries “virtuously” to point away from itself.

In the prayer Jesus taught his disciples we pray, “Deliver us from evil.” To pray this with understanding we need some sense of what evil is. Alas, privatized, dualistic Christianity often reduces it to personal temptation and Harry Potter and ninja turtles. It certainly includes personal temptation but involves far more than that. Indeed, “When you see the world through blinkers, knowing the truth does not make you free.”[1] Jesus knew about evil and temptation. Before he began his public ministry, he was tempted by Satan through devious quotations from the Bible to set aside his mission that would lead through the cross. Jesus’ personal temptations had cosmic implications, and evil is not just personal but social, national, international, political, economic, and structural. Jesus came to lead the whole creation in an exodus from sin and evil, precisely because sin and evil affect the whole creation.

I am told that a reason why some of the Reformed churches in the Netherlands were so resilient in opposing National Socialism during WWII was that churches took the threat seriously. They were able to do this because they took being well informed seriously. As the threat of Hitler loomed over Europe, church study groups got hold of Mein Kampf and read and studied it. They became informed citizens, realized just what they were up against, and were thus prepared to recognize and to oppose the evil spreading out across Europe.

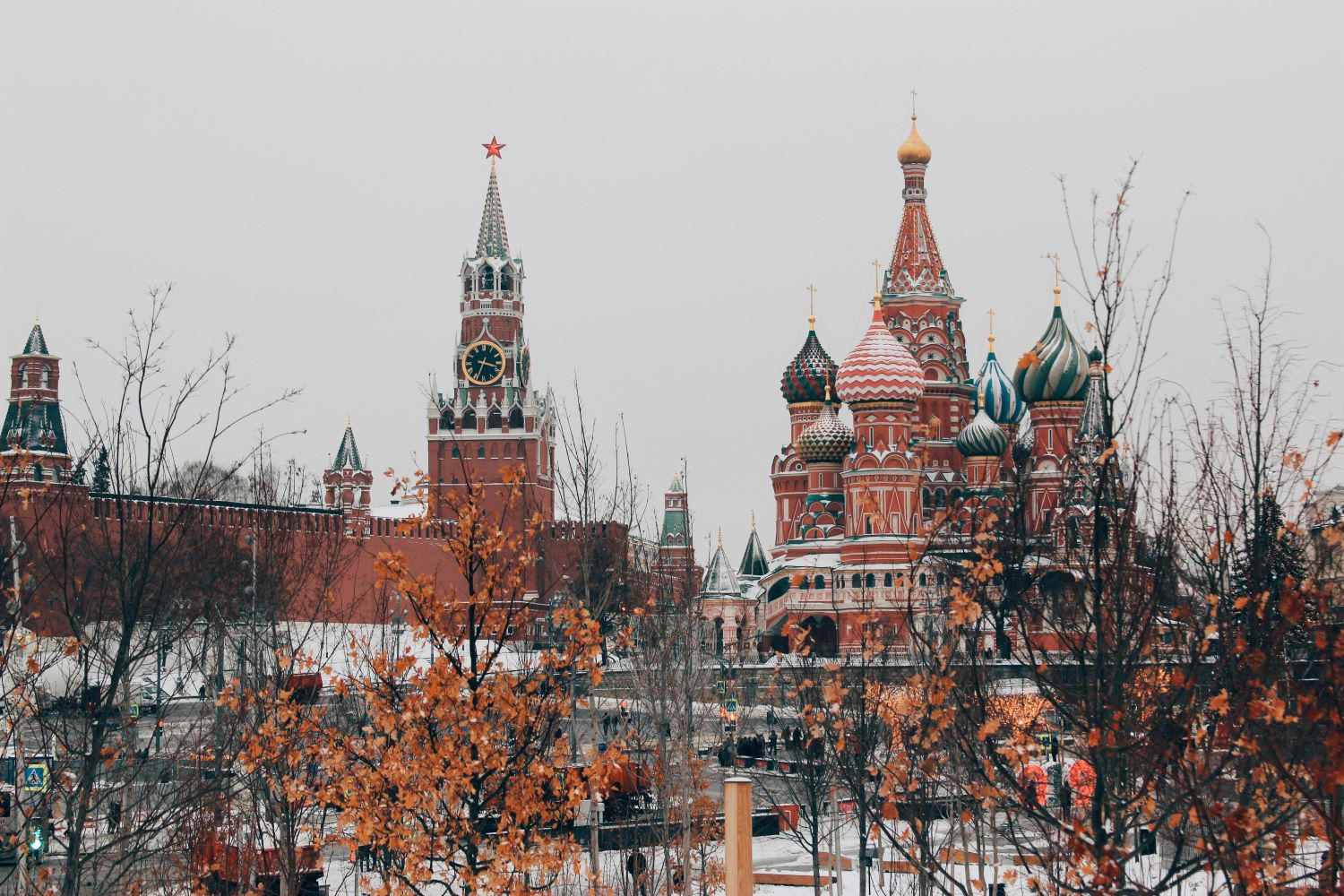

Evil has not gone away. But do we care, and are we equipped to recognize it? It is hard not to see that what the Putin regime is doing in Ukraine is evil. Murder, war crimes, and genocide are unquestionably evil. How is it that this war has suddenly – or so it seems to many of us – erupted in Europe just as we are staggering out of the pandemic?

To understand what is going on in Ukraine today we need to understand Putin and his regime. Amidst the tsunami of disinformation that is generated nowadays, not least by the Putin regime, being informed is more important than ever. Disinformation and fake news are successful when they create just enough doubt to blur the truth, leaving us unsure about whether or not that which is evil is really so. Catherine Belton’s acclaimed Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and then Took on the West (London: William Collins, 2020) is an important recent book in this regard.

Belton’s narrative is detailed and thorough, and I can only provide a broad sketch of it here. The subtitle articulates a central theme of the book. Putin himself was a KGB officer in East Germany where he worked with and alongside the dreaded Stasi. A former member of the far-left Red Army faction testified that Putin “worked in support of members of the group, which sowed terror across West Germany in the seventies and the eighties” (36). During this time, he seemed to have developed an interest in deadly poisons that leave little or no trace (42). When the Soviet Empire collapsed the KGB was initially marginalized, but it did not just disappear. Especially in St Petersburg, where Putin had become deputy mayor, the KGB regrouped and fought for power and wealth at all costs. When Putin moved to the Kremlin and began his rise up the ranks, he took all these contacts with him, and once he became president after Yeltsin, the KGB was, as it were, back in power. “Putin’s rise to power did of course amount to the takeover by the KGB of the Kremlin” (196).

Putin soon evolved into a brutal leader for whom the end justified the means. His first term as president was “drenched in blood and controversy” (11), some of which remains unclear because of cover-ups. With his KGB cronies increasingly occupying key government positions, Putin set out on the path towards absolute control of Russia. The media was an early target. Already in St Petersburg, Putin had used his position for corrupt enrichment at the bitter expense of the people. Under Yeltsin the oligarchs that emerged were disdainful of the former KGB. When Putin became president, and his anti-democratic tendencies became apparent, some of the oligarchs opposed him. One of the wealthiest of these was Khodorkovsky. Eventually Putin had him arrested and his trial “changed everything in Putin’s Russia. The pressure Sechin had brought to bear on the judges, the speed of the appeal process, the lack of substance to the charges, had brought the court system irrevocably under the siloviki [the strongmen]” (303-304). It also brought the oligarchs quickly into line. Khodorkovsky spent ten years in prison.

Putin and his KGB colleagues recognized that communism had failed and blamed it for many of Russia’s woes. Indeed, one reason Putin became prime minister and then president was to prevent the communists from recapturing the presidency. However, they needed a new vision to hold Russia together under their control. A threefold cord emerged in this regard: autocracy, territory and love of the fatherland, and … the Orthodox Church. Before he became president, Putin broadcast his religious beliefs, and the KGB men who came to power alongside him steadily followed him in his attachment to the Russian Orthodox Church. Belton notes that, “From the beginning, they were searching for a new national identity. The tenets of the Orthodox Church provided a powerful unifying creed that stretched back beyond the Soviet era to the days of Russia’s imperialist past, and spoke to the great sacrifice, suffering and endurance of the Russian people, and a mystical belief that Russia was the Third Rome, the next ruling empire of the earth” (258).

This surprising attachment to the church seems to have been a matter of expedience. Putin, like Donald Trump, does not seem to know the Christian faith or the Bible well, and Belton relates an illuminating story of Putin being taken to a service on Forgiveness Sunday. His friend informed him that he should prostrate himself before the priest and confess his sins. Putin replied in astonishment, “I am the president of the Russian Federation. Why should I ask for forgiveness?” (259).[2]

Belton published her book, of course, before the recent invasion of Ukraine, but she does discuss the pro-Western revolutions in Ukraine and Georgia. “It was the worst nightmare of Putin’s KGB men that, inspired by events in neighbouring countries, Russian oppositionists funded by the West would seek to topple Putin’s regime too” (271). In both cases, lies and disinformation preceded Putin’s invasion of Georgia and then Crimea. The pretext of denazification is nothing new.

As with Browder’s Freezing Order, Belton explores the West’s failure to confront Russia with serious consequences for these invasions and the deeply disturbing ways in which Westerners enabled tainted money to pour into the West from Russia. She has a chapter entitled “Londongrad” and writes of London that, “The city was awash with Russian cash. But instead of Russia being changed through its integration into Western markets, it was Russia that was changing the West. … It was as if a virus was being injected into it” (352). Indeed, Belton’s book started out as an investigation of the KGB takeover of Russia, but as her research developed something even more frightening came to the fore: “the billions of dollars at Putin’s cronies’ disposal were to be actively used to undermine and corrupt the institutions and democracies of the West” (15). She notes of the West that its “lack of principles has brought the West to the consequences it is experiencing now” (497). Prophetic words indeed.

The level of corruption that Putin presides over is staggering. The leak of the so-called “Panama Papers” and the work of activists like Browder (see Freezing Order) exposed some of the extent of the corruption and the collusion of Western institutions.

With his speech at the February 2007 Munich Security Conference, Putin put the West on notice when he attacked NATO, the West, and America. Here he gave voice to the KGB mistrust of and hatred for the West. An irony, of course, is that Russian money tends to be held in the West and the oligarchs clearly revel in the most lavish Western lifestyles, top schools for their children, and the freedoms.

Belton’s final chapter is on the KGB network and Donald Trump. When the news came through to the Russian parliament in 2016 that Trump had won, the whole hall leapt to their feet in applause and celebration (476). Trump’s strange admiration for and deference to Putin remains to be fully explained. Belton argues that “in the impeachment probe and the 2020 presidential race, the clash between liberal values and a Putin-style corrupt authoritarian order was reaching a denouement” (488).

Belton’s narrative is profoundly disturbing, searing, and illuminating in so many ways. In one sense the Putin regime and the failure of the West are one massive example of the profound truth of 1 Timothy 6:10: “the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil.” This kind of evil is by no means confined to the Putin regime, as demonstrated by the enablers in the West and those keen to feed at the Russian cash trough with no concern for where the money came from or how it was acquired.

A terrible grace of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is that it appears to have awoken Western and non-Western democracies from their slumber. Putin appears to have badly overreached this time, and we need to make sure he has. The rush of diplomacy before the invasion and especially the revealing of intelligence about Putin’s plans before he acted stripped away the predictable propaganda and false flag operations, flushing Putin out into the open so that we could see him for what he is. Let us not forget.

Some serious soul searching needs to be done by democratic nations for our complicity in what has led up to the invasion of Ukraine, and our most basic commitments and freedoms need to be rediscovered and shored up. Evil is real, including in politics, and whether it is in our midst or in Russia we need to be able to name it for what it is.

That the Russian Orthodox Church should be part of the Putin regime’s threefold cord is a tragedy. Jesus warned about the danger of his disciples losing their saltiness. In an incisive article titled “Toxic Patriarch: How Putin Weaponised the Russian Orthodox Church,” Mark Drew concludes of Patriarch Kirill: “May God grant him a merciful hearing before the dread judgment seat, as the Orthodox liturgy prays. But the judgment of history may not be so merciful.”[3] In his People of the Lie, Scott Peck notes that evil is drawn to religion, because it can there most easily masquerade as the light. We should take note.

There is no fun or sense of triumph in naming evil. Unlike Putin and Trump, Christians in mainstream denominations like my own are forever confessing our sins. That is as it should be. We are the sick, we are those who too often are complicit in evil ourselves, and thus we are those who need the medicine of the gospel.

Citizen K

This is a film worth watching. In my review of Putin’s People I refer to the arrest of the oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky as an important turning point in Putin’s reach for absolute power. Citizen K is a 2019 documentary about Khodorkovsky. The documentary tracks his rise to wealth and influence and emerging confrontation with Putin as he started to recognize the importance of democracy in Russia. His resilience while imprisoned and the way in which prison formed him is notable. Khodorkovsky is the founder of “Open Russia.”

Craig Bartholomew is director of the Kirby Laing Centre for Public Theology, in whose publication The Big Picture this article first appeared.

[1] Owen Matthews, “Cross to Bear: Can Russia Ever Atone for Putin’s Sins,” The Spectator 16 April 2022, 12-13, 13.

[2] The parallel with Trump is notable: “I am not sure I have,” Trump said when asked if he’d ever asked God for forgiveness. “I just go on and try to do a better job from there. I don’t think so,” he said. “I think if I do something wrong, I think, I just try and make it right. I don’t bring God into that picture. I don’t.” https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-on-god-i-dont-like-to-have-to-ask-for-forgiveness-2016-1?r=US&IR=T

[3] The Spectator 16 April 2022, 14.