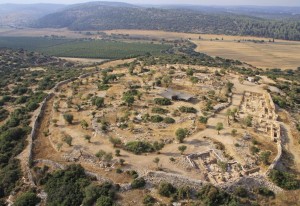

Whenever there’s an archaeological discovery related to the Bible, conflicting interpretations by supposed experts can leave a believer’s head spinning. Take the recent discovery in Israel of a palace from the era of King David. An archaeologist from Hebrew University in Jerusalem says there’s “unequivocal evidence” that David and his descendants ruled at the site. But critics, including some committed believers, say it could have belonged to other kingdoms and that David’s palace likely would have been in Jerusalem some 18 miles to the northwest. Still others claim there is no archaeological evidence that David even existed. Similar confusion ensued this spring when archaeologists discovered a massive complex that may have been an administrative center in Abraham’s native Ur, with division over whether the patriarch’s Ur was at that site or farther north.

Whenever there’s an archaeological discovery related to the Bible, conflicting interpretations by supposed experts can leave a believer’s head spinning. Take the recent discovery in Israel of a palace from the era of King David. An archaeologist from Hebrew University in Jerusalem says there’s “unequivocal evidence” that David and his descendants ruled at the site. But critics, including some committed believers, say it could have belonged to other kingdoms and that David’s palace likely would have been in Jerusalem some 18 miles to the northwest. Still others claim there is no archaeological evidence that David even existed. Similar confusion ensued this spring when archaeologists discovered a massive complex that may have been an administrative center in Abraham’s native Ur, with division over whether the patriarch’s Ur was at that site or farther north.

Since debate often surrounds the discovery of biblical sites, lovers of the Bible may be tempted to give up on archaeology, pronouncing it unhelpful and opting instead to accept Scripture’s historical accounts on “blind faith,” convinced that historical evidence will never be able to confirm biblical accounts. Admittedly, archaeology’s main contribution to biblical studies has been to provide background information. But at the same time, 20th-century theologian Carl Henry reminded us that archaeologists have done significant work in confirming biblical claims (see God, Revelation and Authority, volume 4). Before you give up on archaeology, consider the following:

–In the late 1800s, critical scholars regarded the Hittites as an Old Testament fiction. Except for references in the Bible, there was no evidence they existed. Then archaeologists discovered some 10,000 Hittite and Akkadian texts and over time concluded that Hittites were the dominant power in Asia Minor until 1200 BC.

–Skeptics once regarded as ludicrous the claim that Moses wrote the first five books of the Bible, since writing was thought not to have existed in his day. But thanks to archaeology, we now know that full-fledged phonetically spelled writing existed as early as 2400 BC, well before Moses.

–Critics once claimed the Hebrew exile to Babylon was a myth. Over time though, scholars of the ancient Near East realized, according to archaeologist William Albright, that “there is not a single known case when a town of Judah proper was continuously occupied through the exilic period.”

–Genesis 10:21 names Eber as a main figure in the line of Shem, producing the Hebrews, the Joktanide Arabs, and some Aramean tribes. Numbers 24:24 calls these people groups “Eber” collectively. For years, critics said the name Eber had no historical basis. Then archaeologists discovered in 1976 15,000 clay tablets in Syria, some of which mentioned Eber by name.

The examples of archaeology’s value in confirming the Bible could continue, perhaps most notably with mention of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which helped establish the accuracy of the Old Testament text. But the idea is clear.

Of course, new finds will continue to spur debate, and archaeology is an inexact science. Still, informed believers should never let secular pundits convince them it has no value in confirming Scripture. As the decades pass, new discoveries will add to the list of accounts once scoffed at by skeptics but later established as indisputable facts.

It is not a question if archaeology can help confirm the Bible. It is a question if archaeology can utilize the Bible to help find the truth and the facts.