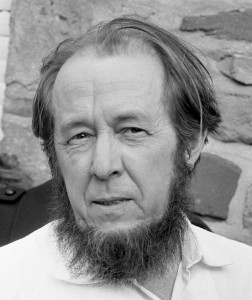

Before his 1978 Harvard commencement address, Russian exile Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was the darling of the American liberal intelligentsia; when he finished, he was a pariah. (The New York Times called him “dangerous” and a “zealot.”1) They were expecting a grateful message, worshipful of their “Great Society.” Instead, he rebuked them for their cowardice, legalism, superficiality, herd instinct, materialism, humanism, and flirtation with socialism.

Solzhenitsyn’s message might have seemed a good fit for a school whose early seals bore the words, In Christi Gloriam (1650) and Christo et Ecclesiae (1692)2. But the school has long since sold its Christian birthright for a “mess of [secular] pottage.”

Solzhenitsyn’s message might have seemed a good fit for a school whose early seals bore the words, In Christi Gloriam (1650) and Christo et Ecclesiae (1692)2. But the school has long since sold its Christian birthright for a “mess of [secular] pottage.”

The founders were long dead when Solzhenitsyn came to the microphone for the 327th commencement. His hearers had little use for talk about “for the glory of Christ” or “for Christ and the Church.” Instead, they were primed to receive a word on “free expression in the face of tyranny” or “the splendor of the unconquerable soul” from this longtime prisoner of the Soviet gulag. They were not at all prepared for the Russian’s prophetic words, such as these that follow:3

This tilt of freedom toward evil has come about gradually, but it evidently stems from a humanistic and benevolent concept according to which man—the master of this world—does not bear any evil within himself, and all the defects of life are caused by misguided social systems, which must therefore be corrected.

The West has finally achieved the rights of man, and even to excess, but man’s sense of responsibility to God and society has grown dimmer and dimmer.

Socialism of any type and shade leads to a total destruction of the human spirit and to a leveling of mankind into death.

It [humanism] started modern Western civilization on the dangerous trend of worshiping man and his material needs.

I am referring to the calamity of an autonomous, irreligious humanistic consciousness. It has made man the measure of all things on earth—imperfect man, who is never free of pride, self-interest, envy, vanity, and dozens of other defects.

Humanism which has lost its Christian heritage cannot prevail in this competition.

We have placed too much hope in politics and social reforms, only to find out that we were being deprived of our most precious possession: our spiritual life.

Alas, neither Harvard nor its adoring constituency fell to its knees in repentance, but prophets are not called to be successful. They are merely called to be faithful, whatever the resistance and reaction. And though their contemporaries may reject their message, their names will enjoy honor where and when honor counts.

Perhaps God will grant Harvard repentance. Perhaps revival will begin with another shocking commencement address, a guest column in the student newspaper, or the conversion of a popular professor. In God’s providence and in God’s time, it doesn’t take much. The founders knew this when they chose Zechariah 4:10 for the title page of the first “catalogue” of their fledgling school—“Who hath despised the Day of small things?”4

———————————–

Endnotes

1 Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Solzhenitsyn at Harvard: The Address, Twelve Early Responses, and Six Later Reflections (Washington, D.C.: Ethics and Public Policy Center, 1980). 3-20.

2 Samuel Eliot Morison, The Founding of Harvard College (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1935), 330.

3 Solzhenitsyn, 23-24.

4 Morison, 420.