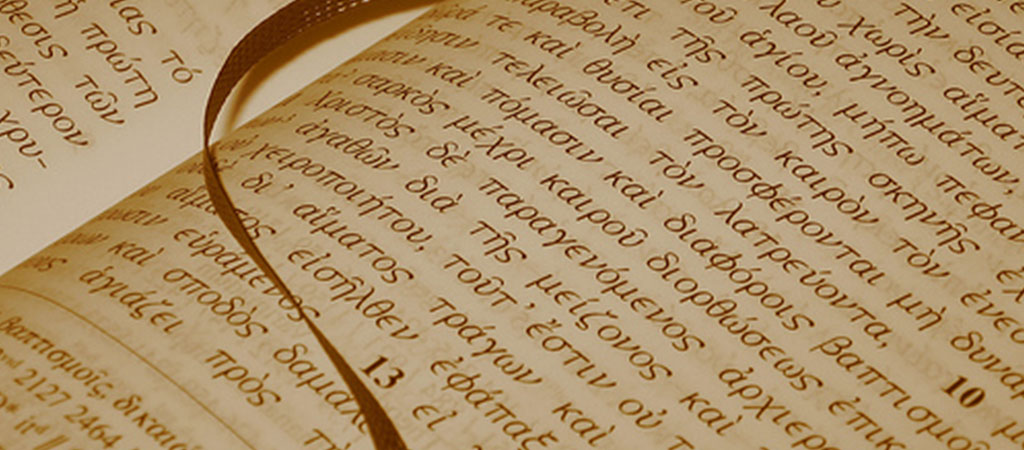

Ad fontes! [Back] to the Sources! was the rallying cry of Renaissance humanism. The exponential growth in Greek and Hebrew learning in the 16th century, alongside the publication of biblical manuscripts and versions, coalesced to produce a tumultuous time in the history of the Christian church—and in particular the way it viewed Scripture. This emphasis on the sources and learning the original languages of Scripture prepared the ground for the sola scriptura rallying cry of the Reformers, as well as paving the way for the numerous vernacular translations that made the scriptures more widely available.

2016 was the 500th anniversary of one of the most significant events in this tumultuous period. Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) published the first edition of his Greek New Testament with Latin translation, Novum Instrumentum, in Basle. This was the first time that the Greek text of the NT had been printed. H.J. de Jonge (Leiden University) describes what was contained in this edition:

The Novum Instrumentum, like the later issues printed in folio format, contains three main parts: the Greek text, Erasmus’ own translation into Latin, and his Annotationes in Novum Testamentum. The Greek and Latin texts are set out in parallel columns on both right and left-hand pages the Greek text forms the left-hand column and the Latin the right-hand. The Annotationes are printed on separate pages. (p. 395, Journal of Theological Studies 35 (1984): 394-400)

Erasmus described this edition as a “revised and improved” New Testament (recognitum et emendatum), and in the dedicatory epistle that to Pope Leo X that accompanied this first edition Erasmus makes clear that his work aims to allow Christendom to “draw from the fount rather than the muddy ponds and rivulets. And so I have revised the whole New Testament (as they call it) against the standard of the Greek original.” It seems that it is the Latin translation that is the focus of this edition with the Greek text and Annotationes providing the support for the changes he made.

The significance of this publication cannot be overstated. De Jonge highlights just how important it was, when he writes:

A shock wave went through Europe in 1516, when a new Latin translation of the New Testament appeared in Basel. For a thousand years, the authoritative text of the Bible had been that of the Latin Vulgate. Now, the authority of the Vulgate was under attack from a competing Latin version. (p.135 “Erasmus’ Method of Translation in his Version of the New Testament” Technical papers for the Bible Translator, 37.1 (1986): 135-138)

It seems amazing to us today that a new translation could disturb a whole continent. Yet, for many in the Catholic Church the very authority of the Scriptures was at stake when Erasmus suggested the Vulgate needed correcting.

It was not only the new translation that changed or challenged contemporary doctrines of Scripture. The publication of the Greek text was also hugely significant when understood alongside the increasing number of people learning the original languages. This increasing importance of philology spurred a dramatic change in the questions being asked of the biblical text, the methods used to answer them, and the expertise required or expected of those who could answer them!

So, what was the significance of his Greek edition of the NT? Why would a new Latin translation send shock waves through Europe 500 years ago? These questions will be discussed in part 2 of this post tomorrow.

Timothy Edwards is editor of the Hebrew program for the BibleMesh Institute. He also serves as academic dean and fellow of theology at New Saint Andrews College in Moscow, Idaho.

Timothy Edwards is editor of the Hebrew program for the BibleMesh Institute. He also serves as academic dean and fellow of theology at New Saint Andrews College in Moscow, Idaho.