Though he had once fought for Athens and then spent his working life in the dogged pursuit of moral truth, Socrates now stood before the Assembly, charged with the twin crimes of atheism and corrupting the youth. He insisted that he had always  acknowledged the gods, and he challenged his accusers to present, as a witness, a single victimized young person. Though none came forth, Socrates was nevertheless condemned to die. Later, awaiting execution, he brushed aside attempts to engineer an escape, saying it would be disloyal to the state. Finally, after considering his own prospects for an afterlife, he drank the poisoned hemlock and died in the presence of his weeping disciples. This sequence of events,[i] occurring in 399 B.C., was one of the great injustices of history—and was carried out in a democracy.

acknowledged the gods, and he challenged his accusers to present, as a witness, a single victimized young person. Though none came forth, Socrates was nevertheless condemned to die. Later, awaiting execution, he brushed aside attempts to engineer an escape, saying it would be disloyal to the state. Finally, after considering his own prospects for an afterlife, he drank the poisoned hemlock and died in the presence of his weeping disciples. This sequence of events,[i] occurring in 399 B.C., was one of the great injustices of history—and was carried out in a democracy.

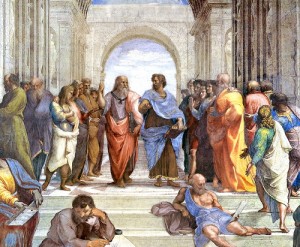

Not surprisingly, Socrates’ devoted pupil Plato was not democracy’s greatest advocate. Plato was also painfully aware of another “democratic atrocity,” the vindictive extermination, in 416 B.C., of all the adult male citizens of the little town of Melos and the enslavement of all its women and children.[ii] So when, in 360 B.C., he penned his great work The Republic, he warned that, in a democracy, “[T]he minds of the citizens become so sensitive that the least vestige of restraint is resented as intolerable.” Finally, “in their determination to have no master they disregard all laws, written or unwritten.” The result: “[F]rom an extreme of liberty one is likely to get, in the individual and in society, a reaction [extending] to an extreme of subjection [namely, tyranny].”[iii] He believed that an egalitarian, democratic culture, based on the idea that all individuals and opinions are of equal worth, could undermine the pursuit of excellence and respect for authority and also encourage envious aggression toward people of ability and wealth. The resulting amalgam of social disorder, fear, and incompetent government created the conditions from which dictatorships emerged.

In the 5th century B.C., all free, Athenian, male citizens were full and equal participants in government at every level: They initiated, discussed, and passed legislation in the Assembly; they were equally liable to do jury service and military service; since all appointments to public office were by lot, even the poorest citizens could wield executive power; and a “quorum of 6,000 citizens could vote to exile anyone for five or ten years simply by writing his name on pottery shards[iv] . . . cast as ballots.”[v] Whilst this system of direct participatory democracy helped to educate Athenians in the arts of government and worked relatively well under wise and inspiring leaders like Pericles, it swiftly degenerated after his death in 429 B.C. Sound society gave way to leadership by demagogues, to class war, to attacks on the property rights of unpopular minorities, and to the persecution of dissident individuals. At the same time, Athenians denied to their allies and dependents the liberty and self-government which they themselves enjoyed. Eventually, Athens, wracked by conspiracies and revolts, fell to her undemocratic rival, Sparta.

The failure of democracy in the land of its birth teaches us an important lesson: Since human nature is fallen, democracy is no guarantor of lasting good government; it is only as good as the values commonly held by the majority of its citizens. It is not enough that they know the laws of their state; they must also show regard for their neighbors, according to the laws of God. When they do, democracies can flourish; when they do not, even the most thoughtfully-framed government will disintegrate.

Sadly, 5th century Athenians, with their many false gods, were only dimly aware of God’s truths and ways. And today, as Western societies turn away from Christianity, so too do their democracies suffer strain, threatening to degenerate into personal licentiousness and government tyranny. Furthermore, as the West seeks to extend democracy around the world, it should remember that where the people are disoriented or ignoble, “rule by the people” is problematic, requiring the safeguard of rights and great patience as cultures seek to rise to their new opportunities and responsibilities. In the last analysis, democracy is not the issue; instead, the moral wisdom of the people is the great essential for a healthy society.

——-Footnotes———

[i] Captured in Plato’s dialogues, Apology, Crito, and Phaedo.

[ii] This was for refusing to abandon its neutrality in the long and disastrous Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.) between Athens and Sparta. For a contemporary account, see: Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, ed. and trans. Richard Livingstone (London: Oxford University Press, 1956), 266-274.

[iii] Plato, The Republic, trans. Desmond Lee (London: Penguin Classics, 1979), 384.

[iv] Ostraka, from which comes “ostracism.”

[v] Patrick Watson & Benjamin Barber, The Struggle for Democracy (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1988), 17.