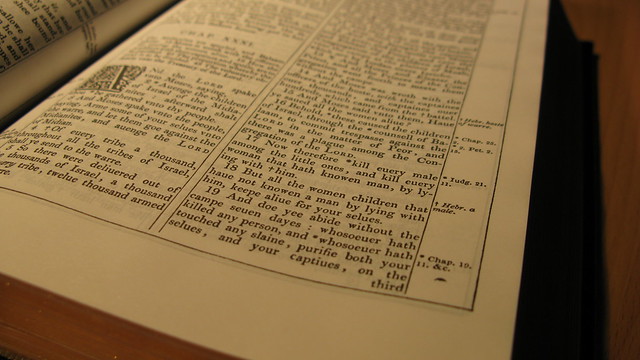

In its December 2011 issue, National Geographic celebrated the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible, noting the massive impact it has had on the English language (among other things). Consider the following:

Most of us might think we have forgotten its words, but the King James Bible has sewn itself into the fabric of the language. If a child is ever the apple of her parents’ eye or an idea seems as old as the hills, if we are at death’s door or at our wits’ end, if we have gone through a baptism of fire or are about to bite the dust, if it seems at times that the blind are leading the blind or we are casting pearls before swine, if you are either buttering someone up or casting the first stone, the King James Bible, whether we know it or not, is speaking through us. The haves and have-nots, heads on plates, thieves in the night, scum of the earth, best until last, sackcloth and ashes, streets paved in gold, and the skin of one’s teeth: All of them have been transmitted to us by the translators who did their magnificent work 400 years ago.

We could add to that list other common phrases that originated with early English Bible translator William Tyndale and made their way into the King James Bible. Among them: “Eat, drink, and be merry;” “powers that be;” “fight the good fight;” “my brother’s keeper;” “salt of the earth;” and “a man after his own heart.” Indeed, the King James Bible is the bestselling English book of all time, with its language sprinkled through works as diverse as the Gettysburg Address, Moby Dick, and the speeches of Martin Luther King Jr. In all, the KJV has sold hundreds of millions of copies in its storied existence.

So its linguistic influence should come as little surprise. If ever you hear someone refer to the Bible as antiquated or irrelevant, remind them that without it, our language would be less colorful, expressive, and rich.