By Henry Blackwell’s calculation, there were three masses of illiterate voters in America in 1895—immigrants in the North, poor whites in the South, and the southern Negro. He compared them to monkeys casting ballots. The solution was clear to his hearers gathered for the Atlanta meeting of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association: Give women the vote. As he put it, “[I]n every State, save one, there are more educated women than all the illiterate voters, white and black, native and foreign.”[i]

The 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted voting rights to black males in 1870, but some states fought to reverse this through poll taxes, literacy tests, and property requirements.[ii] “In Louisiana, for instance, there were 130,334 registered Negro voters in 1896; in 1904, only 1,342.”[iii] But the long-term solution would be the constitutional guarantee of a new voting bloc essentially doubling the white vote. In the words of Southern suffragist Belle Kearney, it would “insure immediate and durable white supremacy, honestly attained.”[iv] She assured her northern sisters that they would one day be grateful as they faced their own invasion of racial and cultural undesirables.[v]

The 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granted voting rights to black males in 1870, but some states fought to reverse this through poll taxes, literacy tests, and property requirements.[ii] “In Louisiana, for instance, there were 130,334 registered Negro voters in 1896; in 1904, only 1,342.”[iii] But the long-term solution would be the constitutional guarantee of a new voting bloc essentially doubling the white vote. In the words of Southern suffragist Belle Kearney, it would “insure immediate and durable white supremacy, honestly attained.”[iv] She assured her northern sisters that they would one day be grateful as they faced their own invasion of racial and cultural undesirables.[v]

Surely suffragists in the North would run from this theme, but many found it acceptable. For one thing, they resented the fact that their husbands and sons had fought a Civil War to give the vote to black males while ignoring the disenfranchisement of their wives and mothers. Second, they were convinced that their vote would be an important corrective to cultural dilution of the voting pool, even benefiting blacks. Third, they were pragmatic.

In the late 1880s, the WCTU’s[vi] Francis Willard toured the South, offering “her ‘pity’ to white Southerners, saddled with the ‘immeasurable’ problem of ‘the colored race . . . multiply[ing] like the locusts of Egypt.’”[vii] Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton refused to endorse the 15th Amendment and readily joined forces with racist newspaper publisher George Train, whose motto was “Women first, and negro last.”[viii]

At one gathering, Anthony called Train’s support for her newspaper, The Revolution, “almost sent from God.” In the discussion that followed, abolitionist Frederick Douglass insisted that Stanton stop “characterizing blacks as ‘Sambo’ and ‘bootblacks.’” Anthony stood her ground, saying that “if the ‘entire people’ could not have suffrage . . . then it must go ‘to the most intelligent first.’” And when fellow suffragist Lucy Stone pled for relief from their campaign against the 15th Amendment, Stanton announced that she “did not believe in allowing ignorant negroes and foreigners to make laws for her to obey.”[ix]

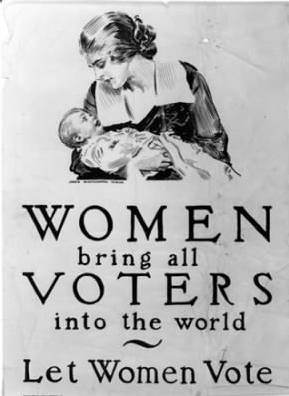

In 1920, the suffragist movement succeeded; the 19th Amendment gave women the vote. Of course, this was a wonderful achievement, thoroughly consonant with the biblical teaching on the dignity and wisdom of women. Not so wonderful was the way in which many American suffragists played upon the racial prejudice of the populace. While Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony have been honored rightly on U.S. stamps and Anthony on U.S. coinage, their legacy is stained somewhat, because their crusade for the 19th Amendment stooped to unsavory measures. They should have known that ends do not justify immoral means.

Endnotes:

[i] Henry B. Blackwell, “Address to NAWSA Convention, Atlanta, Georgia, January 31-February 5, 1895,” in The Concise History of Woman Suffrage: Selections from the Classic Work of Stanton, Anthony, Gage, and Harper, eds. Mari Jo and Paul Buhle (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 337.

[ii] Ann Douglas, Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), 254-255.

[iii] Ibid., 254-255.

[iv] Ibid., 255.

[v] Belle Kearney of Mississippi, speaking at the NAWSA convention in New Orleans, March, 1903. Quoted in Aileen S. Kraditor, The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement: 1890-1920 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1965), 202.

[vi] Women’s Christian Temperance Union

[vii] Douglas, 255.

[viii] Ibid., 256-258.

[ix] One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement, edited by Marjorie Spruill Wheeler (Troutdale, OR: NewSage Press, 1995), 69-70.