I’ve always been intrigued by works of art keyed to biblical texts. In the realm of music, I think of the father and son contributions of Johann Sebastian Bach (e.g., St. Matthew Passion, based on this Gospel’s account of the crucifixion of Jesus) and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (Magnificat, based on Mary’s song of exultation at learning she would bear the Messiah). As for painting, my favorite site is the Arena Chapel on Padova (Padua), Italy, where, in the 14th century, Giotto covered the walls and ceilings with dozens of scenes, from the flight into Egypt to the raising of Lazarus. And, last year, I enjoyed putting together some parable paintings for a seminary magazine, including a Van Gogh Good Samaritan, a Rembrandt Prodigal Son, and a Brueghel rendition of the blind leading the blind.

These were works requiring months and even years to produce, but there is a special type of Christian artistry, works constructed between Sundays for the use in the next Lord’s Day service. In this vein, the elder Bach was known for his prodigious output of worship pieces, where a new cantata was required of him every week (for a total of over 200) when he served as organist of St. Thomas’s Church in Leipzig. For instance, on June 24, 1724, he first performed Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam (Christ our Lord came to the Jordan), marking the Feast of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist (Jesus’ cousin who baptized Him in the Jordan River).

With Bach’s example in mind a few years ago, I turned to an artist in the church that I pastored1 for help with my series on Revelation. I asked if he might bring us one painting or drawing a week, and offered him essentially Wal Mart greeter wages. Happy to say, he was game.

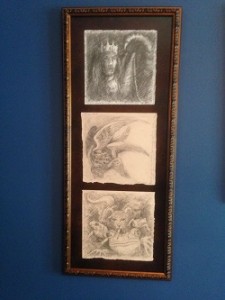

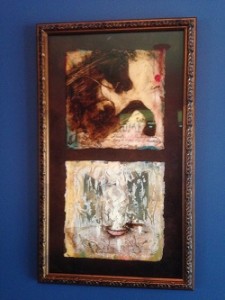

Sure enough, each Sunday he showed up with a fresh work, executed on eight-inch-square pieces of drawing paper—some in pencil, some in pen or paint, some with  encaustic techniques, using heated tar and wax. In one instance, he held the paper over a candle flame to capture the look of black smoke. They featured fantastical, symbolic animals, landscapes and cityscapes, saints and stars.2 We pinned them on the wall to the congregation’s right, saw the collection grow week by week (ten in all), and kept them posted long past the series’ end. (They’re now framed on our dining room wall, where we use them for gospel conversation with guests.)

encaustic techniques, using heated tar and wax. In one instance, he held the paper over a candle flame to capture the look of black smoke. They featured fantastical, symbolic animals, landscapes and cityscapes, saints and stars.2 We pinned them on the wall to the congregation’s right, saw the collection grow week by week (ten in all), and kept them posted long past the series’ end. (They’re now framed on our dining room wall, where we use them for gospel conversation with guests.)

Addressing the Second Commandment in their Larger Catechism, the Westminster Divines condemned drawing any member of the Trinity. Of course, the Commandment goes beyond that to prohibit likenesses of anything whatsoever in “in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth” (Exodus 20:4). But context is important, for following God’s instructions, the Ark of the Covenant cover bore cherubim sculptures (Exodus 37:7), and Solomon’s Temple featured carved palm trees and flowers (1 Kings 6). The issue was idolatry. Much could be said about this concern, but suffice it to say here that we did not worship the drawings.  Rather, we extended Revelation’s word pictures into hand-crafted pictures, in order to advance the strong biblical teaching of the destruction of the devil’s works and the exaltation of the saints in glory.

Rather, we extended Revelation’s word pictures into hand-crafted pictures, in order to advance the strong biblical teaching of the destruction of the devil’s works and the exaltation of the saints in glory.

Of course, artists can get it wrong (and often do in their free-wheeling push for drama, novelty, or provocation), but so can preachers. Yes, the Word has primacy, but not exclusivity, and blessed is the church which regularly enlists the fresh work of musicians and artists to serve with the Holy Spirit in magnifying the holy text.

—————————————

Endnotes:

1 Dan Addington (danaddington.com)

2 E.g., the winged eyes of Rev. 4:8, the crowned locust/horse/scorpions of Rev. 9:7-10; the frogs of Rev. 16:13; the resurrected, ascending witnesses of Rev. 11:12; the river and fruit-laden trees of Rev. 22:1-2; the burning Babylon of Rev. 19:3; the descending New Jerusalem of Rev. 21:9-21; the rise of prayers from a golden bowl of Rev. 8:3-4; seven stars in the Lord’s hand of Rev. 1:16.

//

//

—————————-