Jesus told His disciples that they would be His “witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8). And this wasn’t just a matter of geography. Pentecost, in Jerusalem alone, required a host of languages. And that was just the start, for linguistic missionaries have now translated the gospel into thousands of languages, with thousands to go.

Jesus told His disciples that they would be His “witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8). And this wasn’t just a matter of geography. Pentecost, in Jerusalem alone, required a host of languages. And that was just the start, for linguistic missionaries have now translated the gospel into thousands of languages, with thousands to go.

And so it’s proceeded, from one new language group to the next, whether Slavic (e.g., Russian, Czech, and Bulgarian), Germanic (e.g., Norwegian, English, and Icelandic), or Italic (e.g., Portuguese, French, and Romanian). In English, Jesus’ father appears as “Joseph,” in Spanish as “Jose,” in Finnish “Joosefin,” and in Italian, “Giuseppe.” But it’s the same man.

Then there are the different translations within particular languages. For instance, in English, the King James Version says, in Luke 2, that Mary was Joseph’s “espoused wife, being great with child”; the New Living speaks of her as “his fiancée, who was now obviously pregnant”; and the Contemporary English has her “engaged to Joseph,” “soon going to have a baby.” Some versions are quite literal, essentially word for word (e.g., the New American Standard); others use “dynamic equivalence” (e.g., the New International); still others are “paraphrases” (e.g., the Living). All of these partake of standard English.

But there are also colloquial versions, such as Clarence Jordan’s Cotton Patch Gospel, written in the late 60s and early 70s on a racially integrated farm in south Georgia. Meant to communicate the Word to rural, unlettered Southerners, it features Jesus’ baptism in the Chattahoochee River, calls Peter “Rock,” and uses “Atlanta” for Jerusalem. Here’s a sample from John 6:41-44:

Then the church people raised a stink because he said, “I myself am the ‘loaf’ that came down from on high.” They said, “Why, isn’t this old Joe’s boy? Don’t we ourselves know his mama and daddy? How come he now claims that ‘I have come down from on high’?” Jesus replied, “Y’all quit your bellyaching. Nobody can go with me unless the Father, who sent me, attracts him. And I’ll make him new in the final hour.”[1]

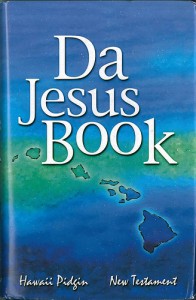

We also have the Bible in “pidgin” tongues, simplified forms of communication, which enable loose, commercial communication between differing language groups. An example is Da Jesus Book, a New Testament from Hawaii,[2] which renders the same passage in John as follows:

Dass why da Jewish guys wen start fo grumble bout him, cuz he wen say, “I jalike da bread dat can make da peopo live. I wen come down from da sky.” Dey tell each odda, “Eh, dis guy, he Jesus, yeah? He Joseph’s boy! We know his fadda an mudda, yeah? So how come he say now, ‘I wen come down from da sky’?” Jesus tell dem, “Eh! Stop grumbling to each odda! My Fadda wen send me hea. No mo nobody can come by me, if my Fadda no bring um. An I goin make dem guys come back alive from mahke wen da world goin pau.

Of course, exacting biblical scholars are not so keen on these idiomatic versions, but they play a role in spreading the word to “the end of the earth.” (That’s why Wycliffe translators spent 20 years developing a Belize Kriol version of Di Nyoo Testiment, released in March 2013.)[3] The same God who made sure the first-century listeners heard Peter at Pentecost is leading translators to pass along his words today to people groups he could not imagine in his day. Thus, they can understand Peter’s warning at Pentecost in Acts 2:40, as “Let god take you outa da bad kine stuff dat da odda peopo stay doing now” (Hawaii Pidgin) and “Save yourselves from this goofed-up society” (Cotton Patch).[4] Amen! Or, as the native Hawaiians put it, “Dass it!”

<!-- RefTagger from Logos. Visit http://www.logos.com/reftagger. This code should appear directly before the tag. -->

//

//