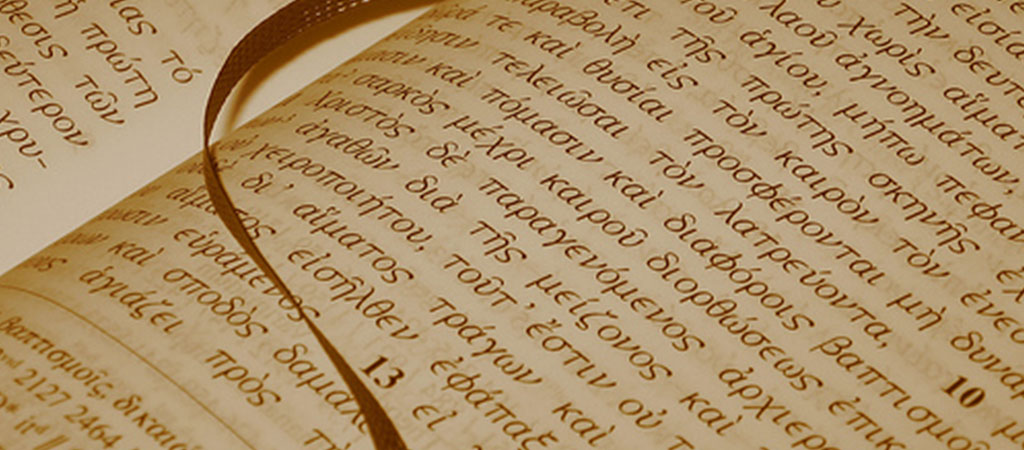

Five hundred years ago, Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam published the first ever printed Greek New Testament in Basle. After publication he immediately went to work on a second edition, which was published in 1519, a third edition in 1522 on through to the fifth and final edition in 1535. This final edition was accompanied by 738 folio pages of annotations. It was Erasmus’ Greek text (and Latin translation) that paved the way for the numerous vernacular translations produced during the Reformation. Erasmus’ NT text also, in time, became the starting point for all subsequent publications of the New Testament up to the first time a text is described as the Textus Receptus (Elzevir’s 2nd edition Greek text published in 1633.) Clearly this first printed Greek text is a significant point in history.

Over the next 100 years or so, alongside these NT texts, numerous polyglot texts were produced (texts that set various versions of the Bible alongside one another so any differences between them were highlighted.) So, 1516 began a period of increased availability of textual information about the text of scripture which, for the western church had, broadly speaking, only been known through the Latin translation for the best part of 1,000 years. This newly available textual information, of course, was not only a great blessing to the church; it also raised great challenges and disputes.

One of the most famous disputes that arose after Erasmus published his Greek text in 1516 surrounded the Comma Johanneum. A quick glance at two modern English translations of 1 John 5:6-8 reveals the issue clearly:

ESV

This is he who came by water and blood—Jesus Christ; not by the water only but by the water and the blood. And the Spirit is the one who testifies, because the Spirit is the truth. For there are three that testify: the Spirit and the water and the blood; and these three agree.

KJV

This is he that came by water and blood, even Jesus Christ; not by water only, but by water and blood. And it is the Spirit that beareth witness, because the Spirit is truth. For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one.

The words in bold are usually omitted from modern translations or have a footnote attached to them asserting that these words are only found in very late manuscripts.

In Erasmus’ 1516 edition there was no, “For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one” in his Greek text. However, it reappeared in his 3rd edition published in 1522 following significant uproar and claims that Erasmus was supporting Arianism by publishing a New Testament that did not contain this famous Trinitarian passage.

In the uproar that followed these missing lines in 1 John 5, Erasmus defended himself, declaring:

If a single manuscript had come into my hands in which stood what we read then I would certainly have used it to fill in what was missing in the other manuscripts I had. Because that did not happen I have taken the only course which was permissible, that is I have indicated what was missing from the Greek manuscripts. (Quoted by H.J. de Jonge, “Erasmus and the Comma Johanneum” Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 56.4 [1980] p.385)

It was not until the 3rd edition (1522) that Erasmus’ Greek text contained these lines, and this after he received a copy of the Greek text contained in the Codex Brittanicus in which the disputed lines appeared. Erasmus, however, suspected that this Greek text had been subject to revision to bring it in line with the Vulgate, as he explained in the annotations, “Although I suspect this manuscript, too, to have been revised after the manuscripts of the Latin world.” Here we find Erasmus taking some of the first tentative steps in what later became the academic discipline of textual criticism. For Erasmus (and modern day textual critics) not all manuscripts are of equal value; not all manuscripts can be trusted. Despite these doubts, however, Erasmus included the words in the 3rd edition of the Greek text. H.J. de Jonge, suggests why:

The real reason which induced Erasmus to include the Comma Johanneum was thus clearly his care for his good name and for the success of his Novum Testamentum. (“Erasmus and the Comma Johanneum” Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 56.4 [1980] p.385)

This small example typifies the challenges that the Erasmus’ Greek text of 1516 set in motion. Over the past 500 years, the available textual information on the Scriptures has increased exponentially. Textual criticism is now a mainstay in biblical studies departments throughout the world, and we can no longer assume that the text of the Bible we read will be the same as that of the person who sits next to us in Church on Sunday. But we also should note de Jonge’s insight quoted above. Erasmus made decisions about the text of the New Testament, but not every decision was solely textual. Reputation and the desire for success played a part! Five hundred years is a long time, but some things don’t change.

Timothy Edwards is editor of the Hebrew program for the BibleMesh Institute. He also serves as academic dean and fellow of theology at New Saint Andrews College in Moscow, Idaho.

Timothy Edwards is editor of the Hebrew program for the BibleMesh Institute. He also serves as academic dean and fellow of theology at New Saint Andrews College in Moscow, Idaho.