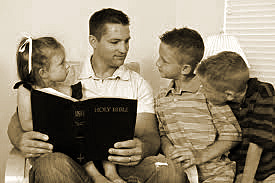

The Westminster Divines wrote the Shorter Catechism beginning with the famous question, “What is the chief end of man?” But it was Thomas Vincent (1634-1678), pastor of London’s St. Mary Magdalen, Milk Street, who helped make it popular. Vincent added his own explanatory notes and then encouraged its use in his church. He asserted that fathers have a unique responsibility to give their children a theological education: “It is not sufficient for you to bring your children and servants to receive public instruction; but it is your duty also to instruct them privately, and at home to examine them in their catechisms.”1 The authors of the Shorter Catechism were so pleased with Vincent’s work that they added their own imprimatur and encouraged its use by believers throughout England: “[W]e judge it may be greatly useful to all Christians in general, especially to private families.”2

Vincent wanted more than to be family-friendly—much was at stake. He ministered in an age hostile to the evangelical faith. In 1662 the authorities ejected him from his pastorate, probably for his refusal to submit to the restrictive measures of the infamous Clarendon Code that required strict observance of all the rites of the Church of England. For the Church to persevere in truth and purity in the face of such persecution, the next generation must know the Bible. Vincent placed this responsibility squarely on the fathers’ shoulders.

Vincent wanted more than to be family-friendly—much was at stake. He ministered in an age hostile to the evangelical faith. In 1662 the authorities ejected him from his pastorate, probably for his refusal to submit to the restrictive measures of the infamous Clarendon Code that required strict observance of all the rites of the Church of England. For the Church to persevere in truth and purity in the face of such persecution, the next generation must know the Bible. Vincent placed this responsibility squarely on the fathers’ shoulders.

Neither Vincent’s practice nor his circumstances were novel. When the early Church suffered persecution, her leaders turned to the method of catechizing, literally, teaching “according to sound” [by ear, not by reading assignments]. Well-instructed believers would be least likely to renounce the faith under fire.3 However, the act of catechizing children did not flourish until the Reformation. John Calvin argued in 1548 that the good of the Church depends, in part, upon the catechizing of children:

[T]he church of God will never preserve itself without a Catechism, for it is like the seed to keep the good grain from dying out, and causing it to multiply from age to age. And therefore, if you desire to build an edifice which shall be of long duration, and which shall not soon fall into decay, make provision for the children.4

In seventeenth-century England, many Puritan pastors may have wondered if the edifice of the Church was falling into decay as evangelicals were forced out of their ministries or, worse, put to death for their zeal. Nonetheless, in the face of such opposition, they urged and equipped parents to catechize their children.5 Well into the nineteenth century, churches and parents considered catechisms a crucial component of their children’s theological education. Times have changed.

In the modern Church (and the modern family), catechisms are considered the ancient tools of a bygone era. Regardless of this current trend, fathers and mothers ought to reclaim the precedent set by their spiritual parents and take the responsibility that is rightfully theirs. This is for the good of the children’s own souls and, ultimately, the purity of the Church.

————————————-

Endnotes:

1 Thomas Vincent, “To the Masters and Governors of Families Belonging to My Congregation,” in The Shorter Catechism of the Westminster Assembly Explained and Proved from Scripture (Carlisle, PA: Banner of Truth, 1980), vii-viii. The Westminster Shorter Catechism was not the first catechism to be published in England, nor was Vincent the first pastor to encourage parents to take responsibility for the spiritual well-being of their children. The Cambridge educated, Baptist pastor, Henry Jessey, for example, wrote a catechism especially fit for little children in 1652. It included, in addition to a section of questions and answers, memorable theological tidbits such as, “The Law was given to show our sin. And wrath that’s due thereby. That we to Christ for righteousness, and life, might always flee.” See Henry Jessey, A Catechism for Babes, or Little Ones, in Baptist Confessions, Covenants, and Catechisms, eds. Timothy and Denise George (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1996), 234. Jessey also, nicely, summarized the Ten Commandments: “With all thy heart love God above/Thy neighbor as thyself so love.” Like Vincent after him, Jessey recognized the responsibility of parents to oversee the scriptural knowledge and spiritual welfare of their children.

2 John Owen, et al, “An Epistle to the Reader,” The Shorter Catechism, v.

3 See Tom Nettles, Teaching Truths, Training Hearts (Amityville, NY: Calvary Press, 1998), 16. For more information on catechism in early Christianity see Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, s.v. “Catechesis, Catechumenate.”

4 John Calvin, “Letter to the Protector Somerset, Geneva, October 22, 1548,” Selected Works of John Calvin, vol. 5, ed. Henry Beveridge and Jules Bonnet (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1983), 191.

5 The Puritan Hugh Peters urged parents to use catechisms in 1630, “if ever your poor infants be driven to wildernesses, to hollow caves, to faggot and fire, or to sorrows of any kind, they will thank God and you, they were well catechized.” See George, Baptist Confessions, 16.