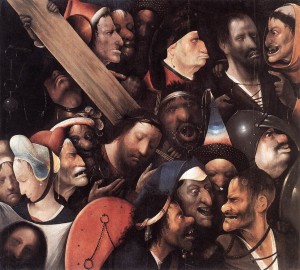

This dramatic 16th-century painting by the Dutch artist Hieronymus Bosch captures the evil in the hearts of Jesus’ tormentors. Behind Him you see the upturned chin of Simon of Cyrene, who helped Him carry the cross. The two thieves who’ll be crucified beside Him are designated by cords around their chests; the penitent one faces a snarling bystander somberly; the other scowls back at his mockers. In the lower left corner is a woman, looking away, holding a cloth bearing Christ’s image.

This dramatic 16th-century painting by the Dutch artist Hieronymus Bosch captures the evil in the hearts of Jesus’ tormentors. Behind Him you see the upturned chin of Simon of Cyrene, who helped Him carry the cross. The two thieves who’ll be crucified beside Him are designated by cords around their chests; the penitent one faces a snarling bystander somberly; the other scowls back at his mockers. In the lower left corner is a woman, looking away, holding a cloth bearing Christ’s image.

Legend has it that the lady is Veronica, who, having compassion on the Lord, rushed to wipe the sweat and blood from His face as He made His way to Calvary. More recently, she appeared in Mel Gibson’s movie, The Passion of the Christ.

As the story goes, she took the cloth, with a recognizable print of Jesus’ visage, to Rome, where an ailing Emperor Tiberius was healed by merely touching it. (Another legend has her traveling with it to France.) Not surprisingly, other Jesus-related relics began to surface throughout the Empire. To distinguish the one in the painting and film from those others, the “original” became known as the vera icon (Latin for “true image”). Then, as the Catholic Encyclopedia explains, “By degrees, popular imagination mistook this word for the name of a person and attached thereto several legends which vary according to the country.” Nevertheless, Veronica has become something of a second tier saint, an object of inspiration and, for some, veneration.

As the story goes, she took the cloth, with a recognizable print of Jesus’ visage, to Rome, where an ailing Emperor Tiberius was healed by merely touching it. (Another legend has her traveling with it to France.) Not surprisingly, other Jesus-related relics began to surface throughout the Empire. To distinguish the one in the painting and film from those others, the “original” became known as the vera icon (Latin for “true image”). Then, as the Catholic Encyclopedia explains, “By degrees, popular imagination mistook this word for the name of a person and attached thereto several legends which vary according to the country.” Nevertheless, Veronica has become something of a second tier saint, an object of inspiration and, for some, veneration.

It’s certainly possible that there was a woman who stepped forward to wipe Jesus’ brow on the Via Dolorosa, but the Gospel writers were not led to chronicle the event. Indeed, there is much that happened in Jesus’ life that does not appear in Scripture. The closing verse of John—21:25—says just that: “Now there are also many other things that Jesus did. Were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written.”

It can be puzzling why some accounts were included and others not. For instance, many have wondered about Mark 14:51-52, which mentions an embarrassing event that occurred at the point of Jesus’ betrayal and arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane: “And a young man followed him, with nothing but a linen cloth about his body. And they seized him, but he left the linen cloth and ran away naked.” (Here’s one rendition by Giuseppe Cesari, from around 1600. The fleeing young man is at the left, the ear-slicing Peter at the lower right.)

It can be puzzling why some accounts were included and others not. For instance, many have wondered about Mark 14:51-52, which mentions an embarrassing event that occurred at the point of Jesus’ betrayal and arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane: “And a young man followed him, with nothing but a linen cloth about his body. And they seized him, but he left the linen cloth and ran away naked.” (Here’s one rendition by Giuseppe Cesari, from around 1600. The fleeing young man is at the left, the ear-slicing Peter at the lower right.)

Wouldn’t the Veronica story have been more edifying? Yet, God chose to include the account of the disrobed runaway. Perhaps there was no such woman at all, and it’s just a nice story. Perhaps God knew that a little thing (a woman’s act of kindness to a condemned Jesus) would be blown up into a fantastical thing (a purported healing cloth for the Roman emperor), and He chose not to encourage this cult of the imagination.

As for the young man, there are a half dozen interpretations. Some say it was Mark himself, who later proved to be a disappointment to Paul on his first missionary journey, but then served admirably as a Gospel writer under the preaching of Peter. This would point to the transforming power of Christ in a person’s life. Others say that this reference to an anonymous observer explains how details of Jesus’ arrest and arraignment were available to the writer after the fact. Still others connect it to the terrified man in Amos 2:16 or the white-clad figure in Mark 16:5.

Whatever the correct reading, Mark 14:51-42 is Scripture, and the Veronica story is not—and we should be happy with that, for the Bible is both inerrant and sufficient. As John Piper has explained it, drawing on 2 Timothy 3:15-17 and Jude 3, “The Scriptures are sufficient in the sense that they are the only (‘once for all’) inspired and (therefore) inerrant words of God that we need, in order to know the way of salvation (‘make you wise unto salvation’) and the way of obedience (‘equipped for every good work’).”

As stirring as legends may be, they cannot, indeed, must not, serve as the ground of our hope and blessing. For this would supplant the real ground of our faith, the Word of God, commended decisively to our hearts by the Holy Spirit.

//