The last few years have seen a fair share of books arguing that religion is the cause behind all that is wrong with the world. Although the Christian Church has undoubtedly had its hand in a number of morally dubious activities over the years, a more historical perspective suggests that this is only one side of the story.

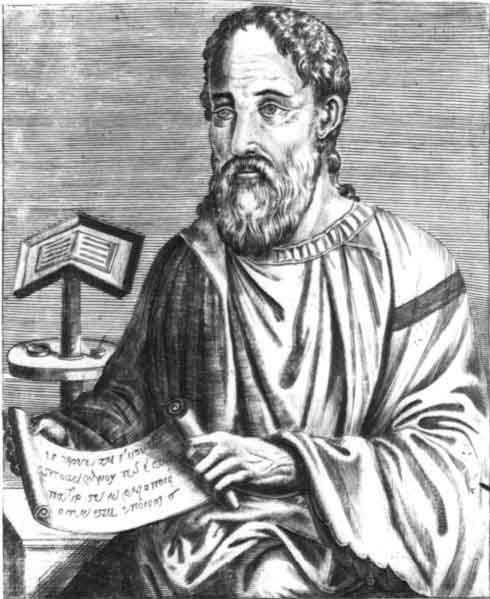

Famine and war had recently afflicted the city of Caesarea, so when the plague hit in the early fourth-century, the populace was already weakened and unable to withstand this additional blow. The populace began fleeing the city, one of the larger ones of the Roman Empire, for safety in the countryside. However, in the midst of the fleeing inhabitants, at least one group was staying behind, the Christians. As bishop of the city and a historian of the early church, Eusebius, recorded in “The Church History” that during the plague,

All day long some of them [the Christians] tended to the dying and to their burial, countless numbers with no one to care for them. Others gathered together from all parts of the city a multitude of those withered from famine and distributed bread to them all.

Eusebius goes on to state that because of their compassion in the midst of the plague, the Christians’ “deeds were on everyone’s lips, and they glorified the God of the Christians. Such actions convinced them that they alone were pious and truly reverent to God.” A few decades after Eusebius, the last pagan emperor, Julian the Apostate, recognized that the Christian practice of compassion was one cause behind the transformation of the faith from a small movement on the edge of the empire, to cultural ascendancy. Writing to a pagan priest he said:

In fact, Julian proposed that pagan priests imitate the Christians’ charity in order to bring about a revival of paganism in the empire.

Julian’s program failed because, among other reasons, the polytheism of ancient Rome was unable to sustain the kind of self-sacrificial love and compassion that Eusebius observed in Caesarea. Cynics might dismiss Eusebius’ account as mere propaganda, since he had an obvious bias as the Christian bishop of the city. However, such dismissal is not as easy with the witness of Julian, for, although he was raised in a Christian setting and thus knew the Christian faith well, he was passionate about his pagan beliefs and sought to undermine the Christian Church. Therefore, he certainly had no reason to present the actions of the Christians in a favorable light.

Christians throughout the centuries have failed terribly at times to live up to their high calling, providing ample ammunition for those wishing to take cheap shots at the Church’s legitimacy. However, alongside such failures are stories that tell how the followers of Jesus Christ went well beyond their non-Christian counterparts – and often still do today – to show compassion to others in imitation of the One who did not consider His own interests, but the interests of others. This side of the story needs to be told as well.

* Julian, Fragment of a Letter to a Priest, 337, in The Works of the Emperor Julian, II, trans. Wilmer Cave Wright (New York: The MacMillan Co., 1913). Julian is not referring to the specific instance that Eusebius cites, but is referring to Christian charity more generally. Elsewhere, Julian stated regarding the Christians, “it is their benevolence to strangers, their care for the graves of the dead and the pretended holiness of their lives that have done most to increase atheism” (To Arsacius, High-Priest of Galatia, 69; in The Works of the Emperor Julian, III, trans. Wilmer Cave Wright [New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1923]). He went on to say that “I believe that we [i.e., the pagans] ought really and truly to practise every one of these virtues.” Julian’s program of moral reform forbade priests from going to licentious theaters and to sacred games at which women were present. He also encouraged priests to demonstrate hospitality by establishing hostels for travelers and distributing money to the poor. As a former Christian, Julian knew the Christian ethic well. Echoing the words of Jesus about the greatest commandment, Julian summarized the requirements for appointment to the pagan priesthood as love for (the pagan) gods and love for man (To Arsacius, 69-70; cf. Fragment of a Letter to a Priest, 336-37).