Each week brings news of fresh horrors in the Middle East as ISIS extends its stunningly evil sway in the region. Through rapes and beheadings and countless indignities, these barbarians have brutalized and tormented essentially anyone who’s not ISIS, including Christians. Those of us in safety marvel at the courage and grace that believers have shown, whether by simply abiding in the land, or reciting Scripture at the moment of their execution.

Each week brings news of fresh horrors in the Middle East as ISIS extends its stunningly evil sway in the region. Through rapes and beheadings and countless indignities, these barbarians have brutalized and tormented essentially anyone who’s not ISIS, including Christians. Those of us in safety marvel at the courage and grace that believers have shown, whether by simply abiding in the land, or reciting Scripture at the moment of their execution.

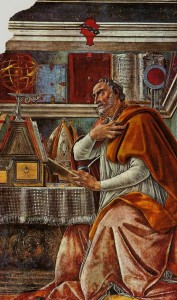

This past week, while reading again the opening chapter of Augustine’s City of God, I was struck by its pertinence to this current situation. Rome was collapsing under its own decadence and “barbarian” invasion, and this great empire, which had slaughtered not only our Savior on Calvary, but also His followers in the Coliseum and Circus Maximus, was blaming its troubles on the Christians. Augustine set out to demonstrate that this was nonsense, and in the course of his argument, he spoke of the character, thinking, and deeds of believers who had undergone great persecution. In so doing, he appealed to Scripture:

- To those dismayed that God made “his sun rise on the good and on the bad, and sends rain alike on the righteous and the unrighteous” (Matthew 5:45), he explained that a system which blesses believers only misleads and corrupts all concerned. As for sufferings, it depends on what you make of them, and what they make of you, for “the fire which makes gold shine makes chaff smoke; the same flail breaks up the straw and clears the grain.”

- To those who muzzled themselves lest their words offend and provoke retaliation, he said that a believer may be blameworthy if, as a “watchman” (Ezekiel 33:6), “he recognizes, but ignores, opportunities of warning and admonishing those with whom the exigencies of this life force him to associate.” (It may be that “he evades this duty for fear of offending them, because he is concerned for those worldly advantages, which are not in themselves discreditable, but to which he is unduly attached.”)

- To those mourning the loss of security and material goods, he reminded them, “We know that God makes all things co-operate for good for those who love him” (Romans 8:28), and that, though impoverished, they may be “rich in the sight of God” (Luke 12:21). Besides, hunger can teach Christians “to live more frugally and to fast more extensively.” And should they be killed, “Christians know that the death of a poor religious man, licked by the tongues of dogs, is far better than the death of a godless rich man, dressed in purple and linen” (Luke 16:19ff.)

- If they lacked a decent burial, they found themselves in the good company of those pictured in Psalm 79:2: “They have set out the mortal parts of thy servants as food for the birds of the sky; and the flesh of thy saints as food for the beasts of the earth.” If they landed in prison, they shared the fate of Daniel (Daniel 1:6).

- Since some had found themselves impressed with a culture that glamorized suicide as a way to escape torture or to “keep oneself pure” from rape or moral compromise, he urged that they submit to Exodus 20:13 (“Thou shall not kill”), which forbids “self-slaughter.” Society at large may honor such figures as Cato and Lucretia for murdering themselves to avoid humiliation, but Christians must not follow suit.

Augustine concluded the chapter by noting that as horrible as their persecutors may be, the people of the “City of Christ the King,” must “bear in mind that among these very enemies are hidden her future citizens.” Indeed, the Saul is a striking case in point: Once an accessory to murder, he became the Church’s leading missionary and theologian. And who knows but what an ISIS foot soldier could one day find the Lord and preach the gospel fearlessly at great peril.